The Commonwealth of Virginia’s new Central Lab project has been a test case in determination. After nearly 15 years in development, a site relocation, uncertainties associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and two and a half years in construction, the $189-million facility is on schedule to deliver by the end of the year. Set on 16 acres in Mechanicsville, Va., the project brings together specialized forensic disciplines for the Virginia Dept. of Forensic Science and the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner into one 281,425-sq-ft facility.

The laboratory will house a wide range of lab spaces, requiring the design and construction team—consisting of construction manager at-risk Skanska USA and architect SFCS—to create dozens of unique spaces with limited repetition. Advanced laboratories for the Dept. of Forensic Science include firearms and toolmark analysis; latent prints and impressions; computer and mobile device forensics; seized drug analysis; toxicology; nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis; and trace evidence examination. There will also be specialized spaces for breath alcohol calibration, evidence storage, research and training.

“As you go through the building, you realize very quickly that there aren’t two spaces alike, other than offices,” says Dereck Alpin, lead architect and project manager at SFCS. “All the lab spaces are unique. They all have different needs.”

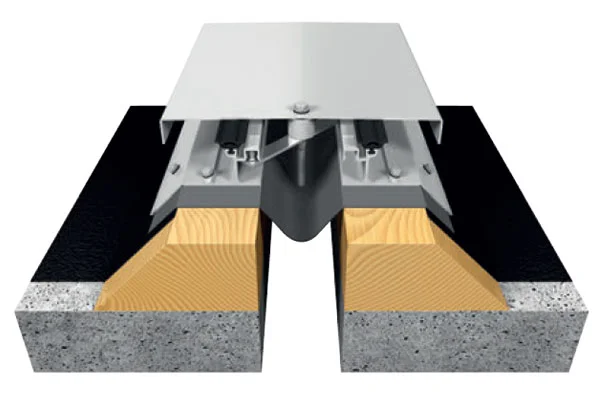

The finished exterior includes brick, metal panel, aluminum storefront and curtain wall.

Image courtesy Skanska USA

Separate, But Integrated

A major consideration of the building program was how to integrate, yet separate, the two user groups. The building is owned by the Virginia Dept. of Forensic Science, while the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner is a tenant. “This works well because we have the same customers by and large,” says Dr. David Barron, deputy director of the Dept. of Forensic Science. “The medical examiner is also a customer of mine, so it works well to have them in our facilities statewide, sharing that same customer base and having the efficiency of us being co-located.”

“It was probably the most challenging functional arrangement I’ve worked on in my 20-year career.”

— Dereck Alpin, Lead Architect, SFCS

Although the two entities are together under one roof, architect SFCS created some segregation between them, designing the building with two wings connected by a central public entry space. Alpin says the decision to split lab spaces between the wings for the two agencies was primarily driven by the fact that the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner is a more “public-facing” entity than the Dept. of Forensic Science.

The three-story south wing houses the Dept. of Forensic Science and is designed with labs positioned directly across the hall from office spaces. The third floor of the north wing is shared administrative space for both agencies. The second floor is training space, and the Chief Medical Examiner labs are at the ground level.

Throughout design, SFCS engaged with a wide variety of users for the various spaces. “It was probably the most challenging functional arrangement I’ve worked on in my 20-year career,” Alpin says. “You have so many more stakeholders. They each have their own needs. They each have their own goals. You have to accommodate those, but also find a way to blend them into one building.”

The Dept. of Forensic Science and Office of the Chief Medical Examiner are linked by a light-filled lobby.

Image courtesy Skanska USA

Structural Savings

The building is a steel structure with a conventional spread footing foundation. Being a laboratory, the floor slabs were designed to mitigate floor vibration. Alpin says that a steel moment frame system would have been the conventional choice, but SFCS worked with the owner to design a brace frame system that met its needs while “saving a significant amount of money on the structural system.” Typical lab bays are 40 ft long, with few, if any, columns to support the spans. “We did everything we could to maximize the bay sizes,” he says. “So as a consequence of that, the floor-to-floor height is 18 feet, which is tall for an office lab building. The second and third floors are 16 feet high, which is also pretty generous. Part of that is due to the depth of the structure.”

Alpin adds that the high floor-to-floor heights also allowed sufficient space for the labs’ significant mechanical system requirements. A mechanical penthouse atop the south building houses a shared chiller plant for both wings. Each wing has its own dedicated air handler system, including separate air handling systems for lab and non-lab spaces.

Although set on a greenfield site, the project was initially conceived as an expansion of an existing facility in Richmond. After studies determined that the expansion would not meet the state’s needs, the project was reworked, requiring the team to seek more funding and approvals. Once the project was able to move forward again in 2021, procurement started at the height of supply chain issues triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Skanska’s contract was finalized in late 2022, and the project broke ground in January 2023.

The Dept. of Forensic Science facility includes a ballistics range.

Image courtesy Skanska USA

To mitigate supply chain concerns, Matt Kidwell, Skanska USA project director, says the team used the firm’s internal strategic supply chain group, which maintains vendor relationships with major manufacturers for building systems. Information from the group was used to build the baseline schedule during preconstruction. The group also provided updates during construction on specific manufacturers that were experiencing issues so the team could proactively address potential schedule impacts with subcontractors.

The Central Lab team was initially anticipating a 90- to 100-week lead time for its electrical switchgear. Through its supplier tracking efforts, Skanska was able to secure its switchgear in 80 weeks. Kidwell says working in such a volatile market when Skanska’s contract required a guaranteed maximum price was extremely difficult. The team was particularly concerned about the price of steel for the lab casework, roofing materials and metals associated with glazing.

“We worked with the owner on that and the prospective subcontractors to develop allowances that we carried in the contract,” he says. “We were able, at the time of the GMP, to provide manufacturer supplier invoices to validate the bid day cost.” Kidwell adds that at the time that the material was fabricated and shipped to site, “we were able to get the updated invoice supplier cost and do a cost reconciliation against that allowance. At the end of the day, we’re making sure we’re not putting a subcontractor at risk for a big financial carry.” From an owner perspective, he explains, “we carried appropriately sized allowances, and we’re returning savings … ensuring that the project comes in within that GMP value.”

Coordinating the setup and function of various labs across different floors challenged the team due to the highly specialized nature of each forensic space and the need for precise equipment placement.

Image courtesy Skanska USA

Coordinated Efforts

To help save time, Skanska adopted the Oracle Primavera Cloud system for the project for pull planning, which enabled trade partners to prepopulate activities up front and online. Kidwell says the original baseline schedule called for footings to be completed along with getting some underground MEP started as steel work began.

“Because of our pull planning efforts for the underground work, we were able to beat durations, get all of our underground in and pour the slab on grade out in front of the steel erector showing up,” he adds. Kidwell estimates that those efforts saved nearly three months in the schedule.

“As you walk through the building, you can really see that bringing the outside inside was a focus during the design process.”

—Mary Ann Petry, Project Manager, Virginia Dept. of General Services

As part of a beta project in the U.S., Skanska also adopted Arrowsight, a relocatable camera system used to monitor the site, especially during night shifts. The footage collected by the Arrowsight system can be analyzed each morning, and any flagged safety issues are sent to the team in short clips, allowing for rapid review and response. The approach has helped Skanska shift from reactive safety management to proactive measures, such as customizing safety training based on common issues observed in the footage.

“We’ve been able to look at trends for things getting flagged that people weren’t necessarily getting hurt, but that could have led to somebody getting hurt,” Kidwell says. “It’s nice in that it was more of a leading indicator versus a lagging indicator.”

This summer, the project hit 1 million work hours without a lost-time incident.

With its finish near, the project design aesthetic is emerging. The finished exterior combines brick, metal panel, aluminum storefront and curtain wall. The building has a flat roof, with parapets and integrated equipment screens to conceal most of the rooftop mechanical equipment. To help create a more comfortable environment for employees, the owners pushed the design team to introduce as much natural light as possible.

In areas where more privacy is needed, frosted glass is used. “As you walk through the building, you can really see that bringing the outside inside was a focus during the design process,” says Mary Ann Petry, project manager for special projects at the Virginia Dept. of General Services.