A failing retaining wall that imposed significant lateral geotechnical loads onto a building’s superstructure highlights the importance of designing retaining structures to manage associated risks effectively, a safety report has found.

A reporter raised concerns about the poorly designed retaining wall in a recent Collaborative Reporting for Safer Structures UK (Cross UK) report.

The issue was discovered when the reporter visited a building opened some years earlier that had experienced repeated problems with a screeded floor finish “popping up” in a corridor.

The building is on a sloping site and sits on two foundation levels, with a 4m high L-shaped retaining wall underneath it, according to the report.

On the uphill side of the retaining wall, at the back of the building, the construction is single storey. On the downhill side of the retaining wall, the building is a three-storey steel frame fronting a level area, after which a series of retaining walls follow the slope down.

The steel frame is founded at ground level and was designed with minimal weight, suitable for a free-standing structure. It is stabilised by steel flat bar cross-bracing.

The corridor with the problematic screed is at ground floor level, on a suspended slab, as it is at first floor level in relation to the steel frame.

The hillside on which the building stands runs behind the building for a considerable distance, according to the report. Groundwater percolates through the soil.

The reporter discovered that the retaining wall was over stressed and failing. They said: “It had been assumed in the design that the soil behind the wall was granular and fully drained, which proved not to be the case.

“Added to this, the retaining wall had been conceived as a rigid cantilever wall: no deflection zone had been allowed. The wall was deflecting forward, and the troublesome corridor slab was being squeezed between the moving wall on one side and the steel frame on the other. This was causing the screed to ‘pop up’.”

The reporter was even more concerned that the horizontal loads being imparted onto the steel frame were more than what the structure’s bracing was capable of restraining.

The bracing was designed to stabilise the superstructure, not restrain a hillside of water bearing silty clay. As there was only one bay of bracing, a single element failure would have destabilised the entire structure, the report found.

The corridor screed issue was therefore an “early warning” of what could have been a much worse situation in which the cross bracing would snap, and the steel frame then collapse, according to the report.

During the investigation, a history of slab settlement behind the wall was also revealed – another early warning, but one that had been missed.

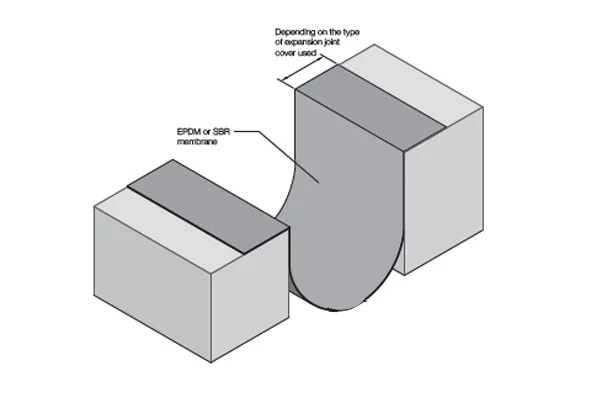

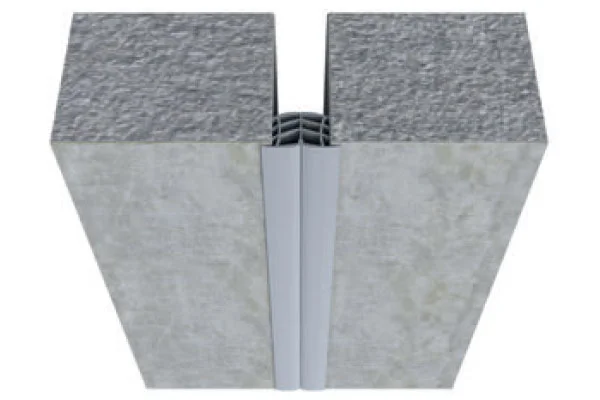

The issue was remedied by improving the drainage behind the wall, building a waling truss in the services corridor that spanned to new anchorage points, and creating a movement zone between the wall and the structure.

The problem was the assumption that the frictional fill behind the retaining wall was fully drained, the reporter noted.

By highlighting this case, the reporter seeks to alert designers and building owners about the potential consequences of lateral geotechnical loads coming to bear on superstructures on stepped sites.

“On a level site, the soil pressures will at least balance. On a sloping site, the loads are eccentric and will push the building. Movement will be resisted by the bracing, which will most likely prove inadequate and snap or deform, thereby destabilising the entire superstructure,” the report said.

It added: “Where there is a retaining wall under a structure, the designer should confirm that their superstructure is either structurally isolated from or is capable to withstand such geotechnical loads as may develop.”

The reporter concluded that the retaining wall is a “critical element” that needs to be designed to resist the full hydrostatic head and with conservative parameters, and given sufficient space to deform as loads are taken up, and with a movement joint.

Cross expert panel comments

Commenting on the report, a Cross UK panel of experts said that it reinforced the need to ensure that retaining wall structures “do not transfer loads to elements that are not intended or designed to resist them”.

The experts noted that less robust designs that rely on dewatering to prevent the build-up of water pressure must be “carefully detailed to ensure effective drainage, adequate discharge capacity, and long-term maintainability”.

They added: “Some of the issues described by the reporter arise from a fundamental misunderstanding of soil mechanics.

“The pressures acting on the rear face of a retaining wall depend on the wall’s ability to deflect and mobilise active earth pressure. If movement is restricted, the wall instead experiences at-rest earth pressure, which is significantly higher than the active pressure.”

They further observed that a reinforced concrete cantilever retaining wall might typically be expected to deflect by approximately height/250.

“In the case described by the reporter, no provision was made to accommodate this movement,” the panel said.

They concluded: “Designers must move beyond the notion that design is simply about calculating stresses and selecting structural members. All structures experience complex movements, and their form and detailing must account for these effects. A deep understanding of the causes and extent of movement, across all materials and structural systems, is essential to good design.

“The retaining wall discussed by the reporter seems to have been treated as a relatively minor part of the overall scheme. It is not clear whether the design team fully appreciated the challenges related to its design and long-term performance, or the potential impact if it were to fail. It is also uncertain whether the team had the right expertise in place to define what would count as a failure and how the related risks should be addressed.”