Construction of South Korea’s 12.5km Incheon Bridge is racing to completion on schedule. Ed Owen reports from the £1bn Asian mega-project, which has relied heavily on off-site precasting and prefabrication to overcome the challenges of working above the sea.

South Korea is a quiet civil engineering powerhouse. Known by some as the Switzerland of South East Asia, around 70% of the country is mountainous.

Consequently Korea has a reputation for tunnelling and bridge building. The Seoul skyline is dotted with steep peaks. These mountains are riddled with tunnels, which give Seoul/Incheon − the world’s second largest conurbation after Tokyo/Yokohama − access to the rest of the country.

West of Seoul the port city of Incheon has been absorbed by Seoul’s expansion to create a metropolis with 24m inhabitants. South Korea’s stunning international airport, built on land reclaimed between two islands, now known as Yeongjong Island is just across the water.

The airport has a motorway link into the heart of Seoul, but links to southern Seoul and the city of Incheon are poor, with commuters needing to take a long detour to make the journey.

Incheon Bridge: fact file

The 12.5km Incheon Bridge is built by the Incheon Bridge Company.

To complete the project, a further 6km of approach roads and bridges will link it to the national road network.

The bridge will link areas of economic growth, on the island of YeongJong where Incheon International Airport is situated, and Songdo, a new economic area on the edge of Incheon city that is already expanding quickly.

Plans are already afoot to double Incheon airport’s capacity in the near future.

The 12.5km Incheon bridge will change this, linking the airport directly to a satellite development city called Songdo built on reclaimed land on the coast of Incheon. It will provide access to future developments on Yeongjong island.

Incheon Bridge Company chief executive and president of Amec Korea, Soo-Hong Kim led the development of the bridge, which started as an obsession of his father’s. “The island that contains the airport is where our family home is. My father is an architect, and is now 95. In 1960 he proposed the Incheon Bridge, which was then a sensational idea,” he says.

“He was trying to raise money and investment from Japan, but the plan did not work,” he explains.

Essential foreign expertise

The financial package put together to build the bridge was novel in many respects. It was the first South Korean Public-Private Partnership (PPP) to be led by a non-Korean firm − Amec.

Soo-Hong says foreign expertise was essential to satisfy the government, which had felt the effects of corruption in the building of its infrastructure during the 1980s, when the country was under a military dictatorship.

In 1994 the Seongsu Bridge in Seoul collapsed, killing 32 people and the following year the Sampoong Department Store collapsed, claiming more then 500 lives (NCE 6 July 1995).

These disasters sparked national outrage − contractors had been found to be cutting corners and corruption was at the heart. The government responded by keeping contractors under very tight control to ensure was no repeat. Projects have layers of engineering design scrutiny and often foreign input to inject new ideas.

“The rubber bearings that the cable stayed bridge rests on are the world’s biggest. They are made with rubber sandwiching steel plates”

Alan Platt, Amec

The £1.06bn Incheon bridge is no exception. Amec was installed as project manager and took a 23% equity stake in the Incheon Bridge Company to get the project off the ground, backed by Australian infrastructure specialist Macquarie and Korean banks IBK and Kookmin. When construction is complete in October, the Incheon Bridge Company will hold the concession to operate and run the bridge for the next 30 years.

The design and build project was handed to a consortium of contractors led by South Korean giant Samsung. Construction was to be fast-tracked, beginning in 2005. (NCE 14 June 2007)

Heading west, the bridge begins as a 2.45km long twin girder viaduct.

This gives way to an 889m long balanced cantilever viaduct comprising six pairs of balanced cantilever concrete box girders, supported by piers 145m apart.

This adjoins the central cable stayed section which spans a busy shipping lane. From there, traffic moves onto another 889m balanced cantilever viaduct, which in turn adjoins a 5.95km twin girder viaduct before connecting into the motorway system on the Yeongjong side.

The long twin girder viaducts run across mudflats and the open sea. They rest on deep piles bored into the mud.

“Steel tubes were driven 60m to 80m into the mud, and excavated using reverse circulation drilling. Once the mud is out, we put in the reinforcement cage and poured the concrete,” said Amec design engineer Kyung Min Kim.

“The viaduct girders were steam cured at 60˚C for 15 to 16 hours to speed the setting process and ensure constant quality”

Moon Gi Jun, Amec

A 2km long temporary jetty had to be constructed across the tidal mudflats at the western end of the crossing to give heavy cranes and other plant access to the viaduct site as the 9m tidal range made it difficult to mount and manouevre plant on floating barges.

In the shallowest water, twin 2.4m diameter piles were used to support the viaduct piers. The number of piles increased with the depth of water to up to eight, 2.4m diameter piles per pier.

Built onto the pile caps are pairs of jumpformed piers, which carry the twin precast girder sections.

For the open sea section of the viaduct, 250m girder sections made up of 50m elements were transported to the end of a completed section of bridge by floating crane.

“The elements are of a standard size − each 50m long and 1,400t, lifted into place with two 2,000t floating cranes from a transporter,” says Amec casting engineer Moon Gi Jun.

“They are post-tensioned in groups of five to make 250m sections, separated by an expansion joint,” he says.

The viaduct sections were cast using self-collapsing Italian formwork presses − the first such machines used in Korea.

“The viaduct girders were steam cured at 60˚C for 15 to 16 hours to speed the setting process and ensure constant quality.

Using precast concrete was vital to the success of the project.

“As little as possible was cast insitu. All 11.5km of the deck was effectively made under factory conditions,” says Amec deputy project director Alan Platt.

A majestic structure

The signature portion of the bridge is without doubt the 1,480m steel deck cable-stayed bridge with 800m main span − the world’s fifth longest.

Holding the bridge deck at a majestic 70m above the water are twin inverted-Y shaped 238.5m tall pylons, the same height as Korea’s tallest skyscraper in downtown Seoul.

Each is cast on top of pile caps built on top of 24, 3m diameter piles.

The central cable stay deck is a prefabricated orthotropic steel box girder made up of 107, 15m long segments.

“For the cable-stayed bridge’s main span, the majority of sections weighed in at approximately 300t. The main span consisted of 51 small sections lifted section by section by derrick cranes mounted on the deck,” says Platt.

The back spans were completed ahead of the main span which was finished at the end of February .

“There is a concrete counterweight in the backspan to compensate for the additional weight in the main span, ordered by the government. The cables are also closer together,” said Platt.

Each of the smaller central span sections were lifted from floating barges using cranes, fixed to the bridge.

The steel deck segments are joined by welding the top flanges, and bolting the bottom lip to their neighbours.

Extraordinary joints

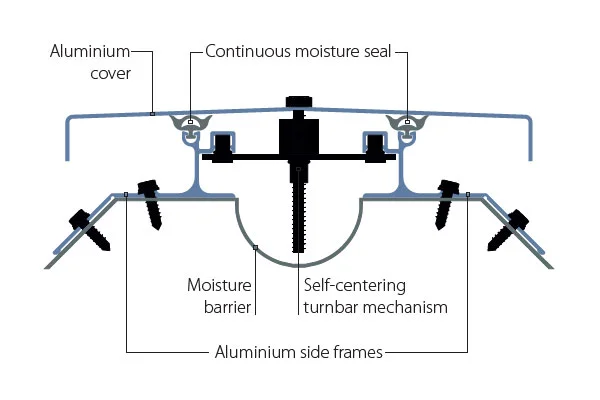

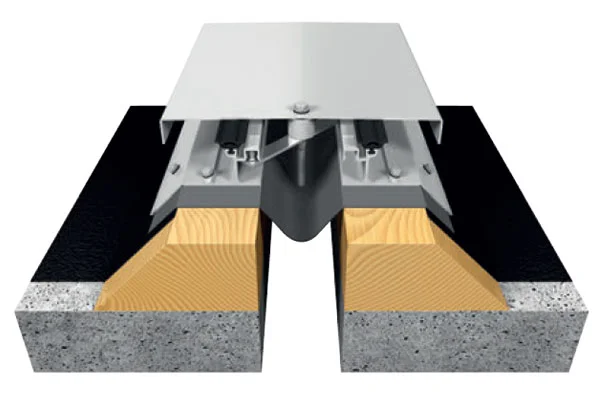

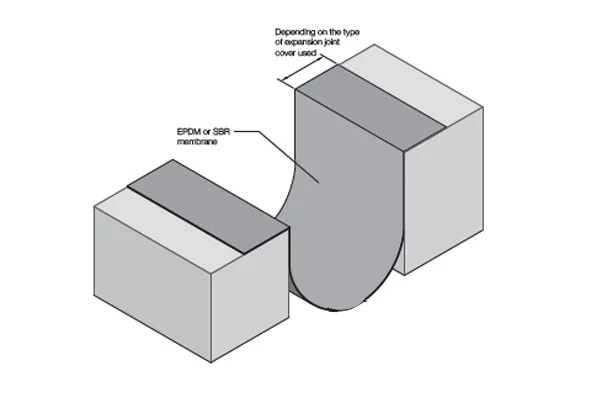

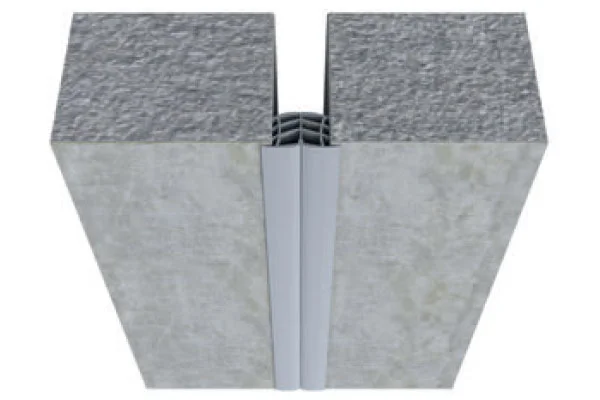

Expansion joints linking the cable-stayed bridge to the approach viaducts are among the largest ever made.

“Mageba supplies the expansion joints − the standard joints separating the 250m concrete girder viaduct sections use five moving parts, and allow up to 200mm of movement,” says Platt.

“The largest expansion joints link the cable-stayed bridge and approach bridge and are amongst the largest in the world. They are also the largest that Mageba have ever made and have 24 moving parts, allowing for some 2,000mm of linear movement, plus lateral movement from wind loading.

“The rubber bearings that the cable-stayed bridge rests on are also the world’s largest. They are made with Yokohama rubber, sandwiching steel plates with vulcanised rubber,” he says.

“For the cable stayed bridge’s main span, the majority of sections weighed in at approximately 300 tonnes”

Alan Platt, deputy project director, Amec

On the Yeongkong Island side of the cable-stayed bridge, a second balanced cantilever viaduct connects to a 5.95km twin girder viaduct taking the crossing to the land.

The bridge is designed to remain open until wind speeds reach 72m/s.

Checks and monitoring

Checking has been an important part of the way the government’s monitors the construction process − a legacy of the 1990s collapses. There are three levels of checking.

A joint venture of Halcrow, Arup and Korean consultant Dusan checks contractor Samsung’s designs.

Above it, a design supervisor − Korean firm Yooshin − is employed directly by project managers Amec.

Then there is the government design deliberation committee, employed by the government’s Korean Expressway Corporation. It scrutinised designers and contractors during formal interviews with a 10-strong board of academics and engineers.

Yooshin also checks the project’s quality, safety and environmental impact but in a separate team, sponsored by the government.

Breaking new ground

That the project was also to break new ground in so many different areas, and to a compressed timescale is due, according to Soo-Hong, to the influence of non-Koreans.

Korea is a highly ordered society where job titles determine your status, and even what sort of car you should drive.

Foreign workers fall outside this system and this enables the team to work more flexibly.

“I thought about PFI about 11 years ago,” says Soo-Hong.

“It started with contractors, but banks were not happy lending to contractors, so we started to make a bidding team that would keep the quality and beauty of the bridge. An additional difficulty was the short time to build the bridge.”

He says that Amec’s project management team within the Incheon Bridge Company gives the Amec workers the ability to sidestep many cultural issues that may have dogged an all-Korean team.

Soo-Hong, a committed Anglophile, believes that this model can be rolled-out in Korea, using cultural exchange programmes to transform the way Koreans think about themselves and conduct business.

The final touches to the bridge are now being completed.

These include huge 25m-diameter ship impact protectors, road surfacing and the completion of the toll station − itself a significant structure.

Rapid development

The Incheon port area

With land at a premium in Seoul, development is moving at breakneck speed in a way reminiscent of mega developments in Dubai.

Where Korea differs from Dubai is that it has an expanding economy with real, not speculative, demand for housing.

The Incheon Bridge is one mega project that has a practical purpose − to link two rapidly expanding areas. It links Incheon’s port area at Songdo to the international airport. Both of these areas are mega-projects in their own right.

Incheon airport was built by demolishing a series of hills, and using the material to reclaim 138 km² of land from the sea on Yeongjong Island. The airport has plans to double in size and construct two additional runways plus a third terminal as it competes to become the major airport hub in south east Asia.

Songdo is a metropolitan development which will eventually house 250,000 people on a 53 km² plot, again reclaimed from the sea. With nothing but empty plots just two years ago, the area is now a self-contained new city, complete with high rise and a Jack Nicklaus designed golf club reputed to cost $2M to join. The third, smaller, area on the edge of Incheon is Cheongna, which houses the new Seoul University and finance centre on an 81km² plot.

Korea is also developing its own high speed rail network − the KTX that uses French TGV technology − to link the north and south of the country. The KTX links Seoul with the cities of Daejeon, home to the world’s most advanced nuclear fusion reactor, and Busan, where the Busan-Geoje fixed link mega project is also underway (NCE 15 January).

- 138km2: Land reclaimed for Incheon International Airport

- 250k: Population of the new Songdu city built over the last two years