Top left: SGT Selena York, 5th Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery Regiment (Long-Range Fires Battalion), 1st Multi-Domain Task Force, repairs the electrical connector pins on a High Modility Artillery Rocket System during Operation Maneuver, as part of Salaknib 25, on Fort Magsaysay, June 17, 2025.

Bottom Left: Soldiers from the Transformation in Contact-enabled 2nd Mobile Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, pull security after exiting a CH-47 Chinook while conducting an air assault exercise during Operational Maneuver at Camp Dela Cruz, Philippines, June 19, 2025.

Top Right: Soldiers work alongside Philippine Army Soldiers to offload equipment on the 8th Theater Sustainment Commands LCU to conduct overseas movement during Operation Maneuver, the culminating event of Salaknib 25, on June 22, 2025.

(Photo Credit: SPC Matthew Keegan, SPC Aiden O’Marra, and PFC Jose Nunez)

VIEW ORIGINAL

Large-scale combat operations (LSCO) in the Indo-Pacific demand more than traditional logistics. The region’s sheer scale, its island geography, and the range of operational environments require a completely different approach, one that blends strategic foresight with adaptable, distributed sustainment. The tyranny of distance makes even basic resupply challenging, let alone sustaining tempo and survivability during combat. In this context, combat readiness is not a box to check, but something we must build deliberately over time and work to maintain under contested conditions. Sustainment is not a supporting function. It is the decisive factor that enables tempo, endurance, and survivability in LSCO.

Historical Lessons and the Pacific Theater’s Unique Demands

The challenges of sustaining operations in the Pacific are not new. During World War II, the Army had to quickly figure out how to keep troops supplied across thousands of miles of open ocean. The island-hopping campaigns depended on massive logistics efforts that touched nearly every part of the theater. The Army played a key role in setting up and running logistics hubs across Australia, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and the Philippines. These efforts supported major campaigns like Guadalcanal, Leyte, and Luzon. It was not just about moving supplies. It meant building forward bases, depots, and transportation networks to keep operations going across a chain of remote islands. Bases in Hawaii and Australia and forward hubs like Guadalcanal were part of a larger system built to support sustained combat power. Those lessons still matter today. They remind us that shaping the battlefield with Army prepositioned stocks (APS), forward infrastructure, and assured regional access must happen long before the first shot is fired.

Prepositioning and Distributed Logistics

One of the most direct ways we build readiness before the fight is through APS. APS 3, also known as APS Afloat, for example, provides a scalable, responsive option to rapidly support combat operations without overcommitting forces or resources. Ships can be repositioned as the situation evolves, giving planners flexibility when timelines are tight.

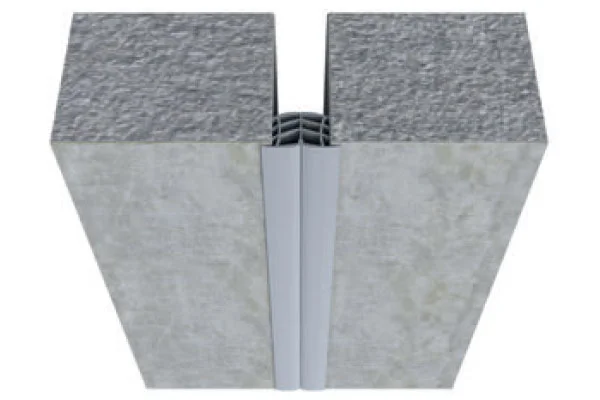

Forward logistics nodes help reduce resupply timelines and extend operational reach. They cannot be fragile. These locations must be hardened, redundant, and camouflaged to endure enemy action. Their construction supports endurance during conflict and signals a serious investment in pre-conflict preparedness. This is a foundational component of combat readiness.

Joint theater distribution centers (JTDCs) are essential in tying this architecture together. They do not just move cargo. They orchestrate the entire sustainment network while countering the adversary’s capability to contest logistics. Strategically positioned, JTDCs manage multimodal distribution, sort materiel, and connect directly with host-nation infrastructure. When done correctly, they transform logistics from a burden into an advantage and are key to building and sustaining tempo in LSCO.

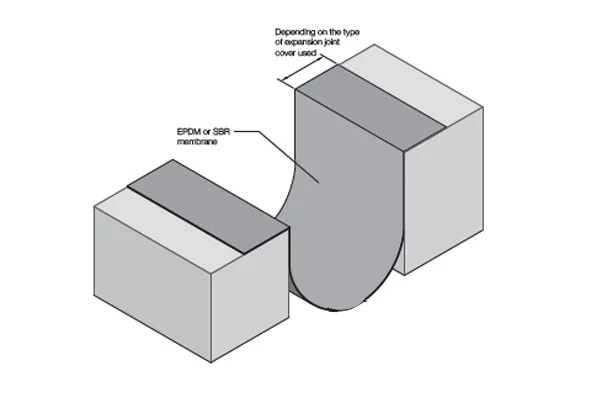

Army watercraft are often overlooked in discussions about distributed logistics. These platforms are uniquely suited to the Indo-Pacific, where long distances and limited infrastructure make fixed ports a liability. Army watercraft provide intra-theater mobility, enabling sustainment deliveries directly to austere or degraded shorelines. They support logistics-over-the-shore operations, reduce dependence on vulnerable port infrastructure, and extend the reach of forward logistics nodes. When integrated with modular sustainment packages and coordinated through JTDCs, they give the joint force a level of flexibility that is hard to match by land or air alone.

Working Jointly in the Indo-Pacific

We do not get to choose our neighbors or our terrain. In the Pacific, joint and allied logistics are not optional; they are foundational. The Army does not operate in a vacuum. Our ability to fight and sustain the fight depends on close integration with Navy sealift, Air Force mobility, Marine Corps distributed operations, and partner nations across the region. We must build joint sustainment from the outset.

Exercises like Talisman Sabre and Cobra Gold give us the chance to practice interoperability under real-world conditions. They help us work through potential friction points, such as learning whose comms do not lineup, who cannot share fuel, and who needs lift support. They also build trust, an intangible yet essential component of readiness.

One recent example that illustrates this is Salaknib 2025 in the Philippines. During the exercise, a combined joint force successfully executed a full-scale joint logistics over-the-shore operation, moving vehicles and sustainment supplies ashore without access to a fixed port. In an environment where ports may be denied or degraded by the enemy, that kind of capability is not a luxury, it is essential. Salaknib showed that with partners by our side, we can move and sustain the fight when it matters most.

Sustainment in a Contested, Multidomain Fight

Combat readiness in LSCO cannot assume permissive conditions. Modern sustainment operations must account for persistent threats across cyber, space, air, and maritime domains. It is not just about delivering supplies. It is about doing it while under pressure and constant observation. That means we need supply chains that can adapt. We need decentralized routes, duplicated nodes, and mobile fuel and water systems. Sustainment must be resilient by design, not by luck. Sustainers must be trained and ready to operate through disruption, not around it.

Leveraging new technology can help. Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to significantly improve logistics forecasting and to give commanders better visibility across the supply chain. One example is Project Maven. Originally designed to process large amounts of video and imagery for intelligence, its capabilities are proving increasingly relevant to sustainment operations. In a logistics context, Maven can monitor route traffic in real time and recommend alternate paths before congestion or threats materialize. It can flag infrastructure degradation at forward logistics hubs before systems fail. It can also track equipment movement across domains to maintain accurate asset visibility across a dispersed theater. Maven’s integration with sensors and logistics systems contributes to a more dynamic, real-time logistics common operational picture.

Beyond AI, autonomous resupply vehicles, 3D-printed parts at forward locations, and mobile water purification systems reduce dependency on long convoys or vulnerable infrastructure. But these technologies do not matter if they are not built into our plans and rehearsed in conditions that reflect real-world constraints.

Sustaining Tempo Through Persistent Readiness

Building combat readiness begins at home. Maintenance reporting, inventory discipline, and Soldier-level sustainment tasks must be executed with the same seriousness as field training. LSCO stress every echelon, and only disciplined sustainers keep up. Leaders are just as important as the platforms they run. Sustainment officers and NCOs must be trained to operate jointly, think strategically, and make fast, sound decisions under ambiguous or degraded conditions. Their judgment is what preserves tempo and protects survivability.

What we once called exercises are now rehearsals. These are full-scale efforts to stress-test our systems, expose weak points, and refine logistics processes before they are tested in combat. The goal is not just training. It is making sure that when the fight comes, we are not learning in real time.

Conclusion

Building and sustaining combat readiness in LSCO is not a one-time effort. It is an ongoing investment in posture, in infrastructure, in leaders, and in partners. APS, forward nodes, JTDCs, Army watercraft, emerging technologies, and integrated rehearsals all form the backbone of a resilient sustainment enterprise.

Victory in LSCO belongs not just to the most lethal force, but to the one that is sustained, day after day, island after island. In the Pacific, we will not fight from what we imagine. We will fight from what we sustain.

——————–

CPT Taylor Anderson-Koball serves as the field services officer in the Distribution Management Center, 8th Theater Sustainment Command. She attended the Operational Contract Support Course, Support Operations Course, and the Mortuary Affairs Officer Course. She holds a Master of Arts degree in international relations from the University of Oklahoma.

——————–

This article was published in the fall 2025 issue of Army Sustainment.

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Connect with Army Sustainment on LinkedIn

Connect with Army Sustainment on Facebook

—————————————————————————————————————