✕

Three years ago, architect Michael Murphy announced that he would be stepping down as president and CEO of MASS Design Group, the nonprofit firm he cofounded in 2008, which first made a name for itself for its humanitarian health-care facilities in Africa and has since designed a wide array of projects globally, ranging from memorials to university campuses, including the Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture. When he left MASS in 2022, he told RECORD that he would start a new office focusing on “‘sharing the financial ownership of our built environment more equitably,’ which would entail looking for ‘new creative ways to finance cultural and institutional projects.’” Murphy—who holds an endowed chair at the Georgia Institute of Technology—has since completed his first project with that new firm, Agency Michael Murphy and Associates (AMMA). The building, the Oceana Innovation Hub, in Bridgetown, Barbados, draws students from across the island to study their environment and the changing climate. Murphy spoke with RECORD deputy editor Joann Gonchar about the innovation hub, AMMA’s work on the boards, and the aspirations for the new practice.

Michael Murphy. Courtesy Michael Murphy, click to enlarge.

What was the impetus for starting AMMA? Did you have an “aha” moment?

The big awakening was the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (2018), in Montgomery, Alabama, a project I was so honored to be part of. When we were designing it, I walked the site with Bryan Stevenson [the civil rights attorney who led the creation of the memorial and the other nearby Legacy Sites]. I remember thinking, “this could have a big impact. We should acquire the land around the memorial, and we should look at how we can capture the impact.” But where would that capital come from? We were just trying to raise funds to build the building. Well, sure enough, the project has brought transformational economic development to the city and state. I started to wonder how artists, architects, designers, and community groups could share and participate in the value they create in the world. I realized there needed to be a different structure—namely, one that could distribute ownership—that could own and change the supply chain, that could play a role both in design and in development.

How is AMMA’s way of operating different from that of MASS?

The simplest answer is that, at AMMA, we fund our compensation through project fees, and our employees and partners can be stakeholders and potential owners in the projects we deliver. We also of course pay taxes. But the fundamental difference is that we can leverage a more diverse pool of capital, including investments and ownership, to make a project happen that a nonprofit, by definition, cannot fully access.

How did the commission for the Oceana Innovation Hub come about?

XQ Institute, which is part of the Emerson Collective, Laurene Powell Jobs’s impact-investment group, reached out to me. XQ is working with Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados. Mottley, a total rock star, is trying to rethink how her small island nation deals with climate change, sea level rise, and extreme weather.

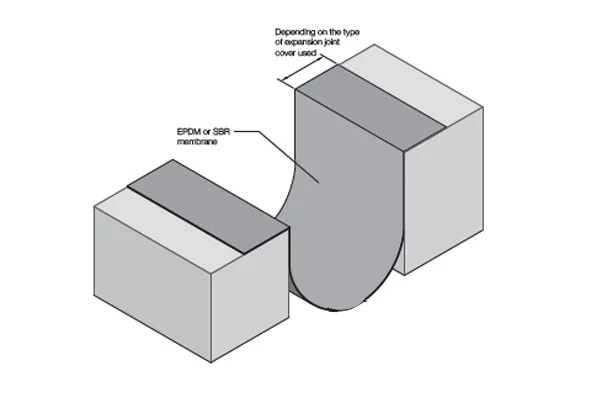

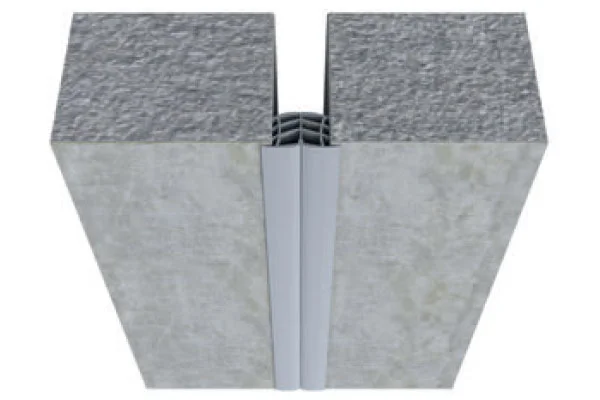

The innovation hub is a prototype—part of a larger transformation of the school system. It is also where Mottley is reintroducing timber construction, in a country that has been deforested and where timber sourcing is now illegal. She’s thinking, “How do we do so, with a supply chain that we can manage and that can contribute to political agency and economic independence?” Architecture is an answer. But we also must design the system underlying it to be successful.

If the timber isn’t from Barbados, where did it come from?

I called Antón García-Abril and Débora Mesa from Ensamble Studio, who are friends and amazing innovators. They have a new initiative, WoHo, which is about prefabrication. I said, “Could you guys help?” And they jumped in and assisted. The project uses wood from Spain, because that is where Antón and Débora are based.

As the prototype is adapted to other sites in Barbados, is the idea to continue sourcing the wood from Spain?

The goal is to use wood from the Caribbean. We’ve started conversations with Guyana, which is deeply interested in creating that supply chain. So, some of this is about being a catalyst, about showing the way we could drive a new market. But we have to develop that market. And we have to have the middle tier of production, including cut shops, fabrication, and shipping. It is a multiyear initiative.

How is the design and delivery of the innovation hub different from a typical architecture commission?

The Oceana project, like almost every cultural project architects work on, is paid for by a mix of philanthropy, private dollars, and government investment. The difference here is that XQ’s vision is for a prototype for schools nationally, regionally, then globally. It is best seen as a pilot of a multiphased, multisite project. The economics of the prototype are different from a typical architectural commission, so should be thought of more as a product than the time-and-materials compensation that architects usually receive for their labor.

Our goal at AMMA, shown in this first phase in Barbados, is to make projects that shift and redesign entire systems. Ultimately, we need to think about the role of the architect as owner, developer, designer, and fabricator. Instead of responding to an RFP for a typical fee, we created the RFP.

Can you talk about the genesis of the prototype’s form?

There’s an incredible history of this type of construction in Barbados. Chattel houses are small wood structures that were built largely by migrant labor. They could be flat-packed and put on donkey carts and moved from farm to farm. They had pyramidal or jagged gable roofs, and were incredibly porous, letting the air move through them. So, during hurricanes, they wouldn’t collapse. They have elements of modularity, movability, breathability, and environmental resilience.

1

The furnishings extend the building’s modular logic, allowing the interior environment to be continuously reconfigured (1 & 2). Photos © Iwan Baan

2

The prototype also takes inspiration from Aldo van Eyck and others in the late mid-20th century who were creating adaptable and adjustable systems. The triangle is a fascinating form because of the infinite variety that can emerge from its assembly, as opposed to the standard rectilinear prefabricated module.

Could the module be adapted for other project types?

One idea for Barbados is to build a residential tower out of the modules that would be the economic engine to fund future schools.

Could it work in other parts of the world?

Two dozen schools were burned in the LA wildfires earlier this year. This model is applicable there. How would it work in the LA climate? Pretty well, especially for natural ventilation. Fire risks would have to be addressed, but a lot of fire mitigation is about treatment of the site around the building.

Paired with operable skylights, louvered shutters control the sun while allowing natural ventilation. Photo © Iwan Baan

An 800-student school based on the prototype is under construction at Chelston Park, not far from the innovation hub, but what else is AMMA working on?

I’m working on a memorial in Boston’s Back Bay to Travis Roy, who was an incredible disability-rights activist. I’ve also been working on a master plan for North Adams, Massachusetts, to take down an urban renewal overpass, which basically decimated the downtown. My partnership is not just in the master planning, but also in imagining new development and the financing of that development once the overpass comes down. The arts center MASS MoCA has also brought me on to rethink housing. It has acquired a 1960s school to create living spaces for artists, to give them places to work on their craft and own a portion of their housing. It goes back to that original premise—in the creative industries, we don’t really own our means of production. If we could own it, we could have skin in the game.

Image courtesy AMMA

Credits

Design Lead:

Michael P. Murphy / AMMA

Design and Construction Team:

AMMA, Office of Jonathan Tate, WoHo, Joseph Steinbok Management Services, Moorjani Caribbean

Consultants:

Mahy Ridley Hazzard, Temha (structural); Transsolar | KlimaEngineering (climate and environmental); EMC (m/e/p); DLA with Sasaki (landscape); EHDD (education design); Studio Amor (local architecture and environmental); TAP Studio (interiors); BCQS (quantity surveying); Bain Planning and Development (permitting)

Architect of Record:

Archis

Concept and Feasibility Report:

AMMA, Animal Name Design, Chris Terrill, EHDD, Jeffrey Miller Architecture and Design (JMAD), NOUS Engineering, RDL, Sasaki, SOSHL Studio, Studio Amor, TAP Studio Transsolar, Yes Praxes

Client:

XQ Institute

Owner/Operator:

Government of Barbados through the Ministry of Educational Transformation

Size:

7,075 square feet

Construction Cost:

$5.7 million

Completion Date:

June 2025

Sources

CLT:

WoHo

Fan:

Big Ass Fans

Millwork:

Kevin Lewis

Furniture:

VS America, Fatboy USA, Diversified Spaces

Custom Furniture:

Rysel McLean

Artist Collaborations:

Marlon Darbeau and Rupert Piggot