Historic Maryland homes often rest on foundations built from fieldstone, rubble, or historic brick that were never designed for modern hydrostatic loads, and these older assemblies are especially vulnerable to water intrusion and moisture-driven decay. This article explains why basement waterproofing tailored to older foundations preserves both structural integrity and historic value, and it maps how material behavior, site drainage, and sensitive repair choices interact to protect these homes. You will learn how stone and brick porosity affects moisture movement, which interior and exterior waterproofing methods are preservation-sensitive, how select foundation repairs restore load capacity without erasing historic fabric, and what routine moisture-control steps prevent mold and long-term damage. Each H2 section below unpacks diagnosis, method selection, moisture management, contractor vetting, and anonymized project examples so owners and stewards can make informed decisions that balance conservation and performance. Throughout, the guidance emphasizes preservation-first techniques, collaboration with preservation authorities, and when to bring in a specialist for site-specific inspection and an evidence-based plan.

What Are the Unique Challenges of Waterproofing Historic Maryland Homes?

Historic Maryland foundations present a set of interrelated challenges rooted in materials, detailing, and site conditions that make standard waterproofing approaches risky without adaptation. Masonry units such as fieldstone and older brick are more porous and salt-laden than modern concrete, so impermeable treatments that trap moisture can accelerate mortar failure and spalling. In addition, older mortars are often softer and incompatible with modern cement-rich products, so repointing or sealing must prioritize compatible lime-based materials to avoid creating rigid, damaging junctions. These material realities combine with Maryland’s variable precipitation and localized high groundwater to elevate hydrostatic pressure on foundations, which in turn drives water through pores and weakened joints; understanding this mechanism is essential before selecting any intervention. The next subsections break down how stone and brick behave and where water most commonly intrudes so readers can recognize symptoms and prioritize targeted diagnostics.

How Do Older Foundation Materials Like Stone and Brick Affect Waterproofing?

How Do Older Foundation Materials Like Stone and Brick Affect Waterproofing?

Older foundation materials such as fieldstone, rubble stone, and historic brick are characterized by higher porosity, heterogenous aggregates, and mortar mixes that permit salt migration and moisture cycling, which influence both deterioration and repair choices. Porosity allows capillary rise and efflorescence—salts deposited as moisture evaporates—so treatments that stop surface evaporation can worsen internal salt damage and frost-related cracking. Mortar composition matters: lime- or lime-cement mortars compatible with historic masonry provide sacrificial, flexible joints, whereas hard modern cement mortars can create stress concentrations and lead to battlement failures. For preservation-sensitive waterproofing, breathable strategies that manage water at the plane of entry while permitting moisture egress are often preferable, and material testing followed by compatible repointing prevents common long-term failures. Understanding these material behaviors leads naturally to identifying typical intrusion points where interventions should focus.

What Are Common Water Intrusion Points in Historic Basements?

Water commonly enters historic basements through specific weak points created by aged detailing and site shortcomings, and recognizing these points guides diagnostic priorities and minimal-impact repairs. Typical intrusion points include deteriorated mortar joints and through-wall cracks where capillary suction and hydrostatic force combine to push water inward, the junction between sill/foundation and floor where settling opens gaps, and floor-to-wall joints that lack modern seals. Exterior factors—poor grading, blocked gutters, and downspouts discharging near foundations—raise local water tables and increase hydrostatic pressure, while failing exterior drains or missing perimeter gutters concentrate flow at vulnerable sections. Detecting these intrusion points requires both visual inspection and moisture mapping tools to distinguish simple leaks from systemic groundwater pressure, which determines whether localized interventions or broader drainage measures are required.

Which Basement Waterproofing Methods Best Preserve Historic Maryland Foundations?

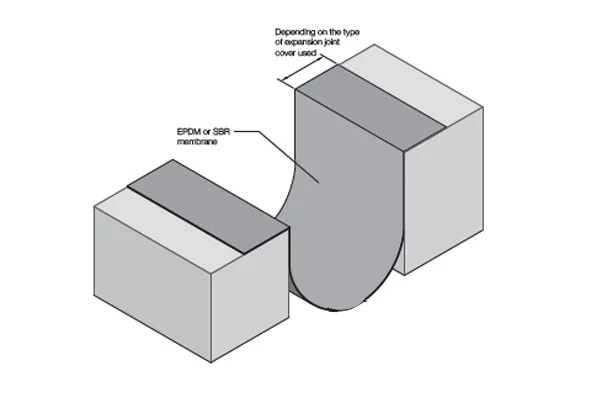

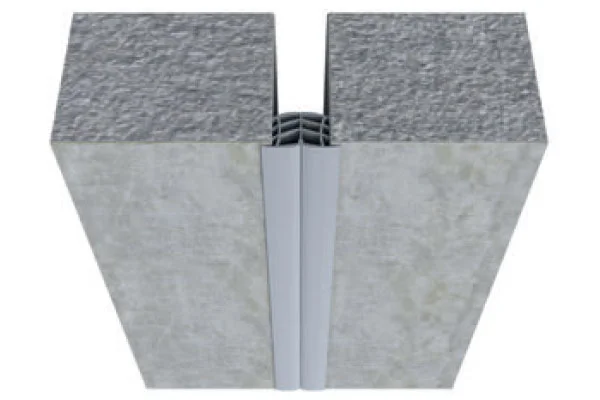

Choosing preservation-first waterproofing requires weighing exterior and interior approaches against invasiveness, breathability, and the foundation type involved, then selecting the least-interfering method that reliably manages hydrostatic pressure. Exterior membrane systems reduce hydrostatic load by shedding water away from masonry but require selective excavation and careful protection of historic fabric; interior drainage systems intercept and remove water with minimal exterior disturbance but change the basement environment and must preserve finishes and features. Sump pumps paired with sub-perimeter drains manage collected water effectively but need discreet placement and backup power planning in older homes where modern mechanical rooms are limited. The table below compares common methods by invasiveness, preservation sensitivity, and ideal foundation types to help owners match strategy to their property’s construction and conservation goals.

Exterior and interior waterproofing options compared for historic foundations:

| Method | Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Exterior membrane waterproofing | Invasiveness: selective excavation; Preservation sensitivity: medium if careful; | Ideal for stone and brick with accessible exterior; reduces hydrostatic pressure when used with perimeter drainage |

| Interior perimeter drainage (French drain) | Invasiveness: limited interior excavation; Preservation sensitivity: high for exterior fabric; | Suitable where exterior work is restricted; manages leaks at the wall-floor junction |

| Sub-slab drain + sump pump | Characteristic: active water removal; Preservation sensitivity: medium; | Best for high groundwater sites where interior options acceptable; requires mechanical maintenance |

This comparison shows that preservation priorities often favor interior drainage and carefully staged exterior work when exterior access would damage historic fabric. After assessing methods, many homeowners call for a specialist inspection to determine site-specific drainage loads, test masonry breathability, and recommend tailored combinations of these approaches.

For historic properties, available service categories typically include exterior membrane installation, interior drainage and sub-perimeter systems, sump pump installation with battery or backup plans, and targeted foundation crack repair. These service types align with the methods described above and form the menu of interventions a preservation-minded specialist will propose after on-site diagnostics and discussion of conservation priorities.

How Does Exterior Waterproofing Protect Historic Stone and Brick Foundations?

Exterior waterproofing protects historic foundations primarily by intercepting and diverting water before it reaches the masonry, thereby reducing hydrostatic forces and limiting moisture cycles that drive salt migration and freeze-thaw damage. The typical preservation-conscious sequence is survey → selective excavation to expose problem areas → installation of a compatible membrane or drainage plane → backfill with free-draining materials and restore surface grading, which minimizes disturbance to historic finishes and landscapes. However, aggressive excavation or incompatible membranes can damage historic masonry, bury original foundation detailing, or trap moisture if the system is not vapor-permeable where needed; therefore, material compatibility and reversible installation techniques are critical. When exterior access is constrained—adjacent buildings, historic landscapes, or review restrictions—interior solutions often provide a less invasive path to reducing hydrostatic pressure while preserving exterior character. Understanding when exterior work is essential versus when interior measures suffice is the next practical decision for owners.

What Interior Drainage Systems Are Suitable for Older Basements?

Interior drainage systems such as perimeter French drains, sub-slab collection, and weeping-tile alternatives collect infiltrating water and route it to a sump where it is discharged mechanically, offering a preservation-sensitive option when exterior intervention would harm historic fabric. Installation focuses on minimal impact: routing drains behind baseboards or beneath new, reversible sub-floors to preserve original flooring and wall finishes, and positioning sump pumps discreetly with attention to noise and backup power to maintain habitability and historic integrity. Sub-slab drains manage groundwater under the floor and can be combined with vapor control layers to moderate humidity without sealing masonry surfaces outright, maintaining a breathable balance. Proper maintenance—regular pump testing, backup power planning, and periodic clearances—ensures these interior systems protect the building while keeping interventions reversible and compatible with preservation goals.

How Can Foundation Repair Maintain Structural Integrity in Historic Maryland Homes?

Foundation repair for historic homes aims to restore load-bearing capacity and stability while minimizing loss of original fabric; this requires accurate diagnosis, minimally invasive techniques, and reversible design where possible. A careful structural survey—combining crack mapping, moisture diagnostics, and targeted probe excavations—distinguishes between cosmetic mortar loss and load-bearing failures that require reinforcement or underpinning. Repair techniques range from compatible repointing and localized grout injection to discreet reinforcement with carbon fiber straps or micro-underpinning; the choice depends on foundation type, extent of deterioration, and conservation constraints. Because interventions like epoxy injection, carbon fiber reinforcement, and underpinning each carry different permanence and visual impacts, professional assessment by a specialist experienced in historic masonry is essential to determine the least invasive, most durable solution. The following table summarizes common repair techniques, their structural application, and preservation impact to guide decision-making.

Comparing foundation repair techniques for historic masonry:

| Repair Method | Application | Preservation Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Epoxy or resin injection | Fills narrow structural cracks to restore tensile capacity | Low visual impact; material compatibility must be evaluated |

| Carbon fiber reinforcement | Adds tensile support to bowed or cracked walls | Minimal thickness and reversible in many cases; careful installation required |

| Localized underpinning/grout injection | Restores bearing capacity beneath settlements | More invasive; can be targeted to avoid full replacement |

Selecting a repair method always begins with diagnostic testing and moisture mapping to ensure the intervention addresses root causes, not symptoms. When evaluating options such as epoxy injection, carbon fiber reinforcement, or underpinning, owners should prioritize reversible or minimally invasive choices and document interventions for future preservation records, which supports long-term stewardship and potential review by preservation bodies.

What Are Effective Foundation Crack Repair Methods for Historic Properties?

Effective crack repair in historic masonry depends on whether a crack is structural or non-structural, the materials involved, and the need to preserve original mortar and stone or brick faces. For non-structural cracks caused by shrinkage or minor settlement, compatible repointing with lime-based mortars restores weather resistance and aesthetic continuity while allowing the wall to breathe. Structural cracks requiring load restoration may benefit from injection with epoxy or specialized resin to bond masonry units, supplemented by external stitching or discreet carbon fiber reinforcement for added tensile strength. Selection criteria include crack width and pattern, moisture presence, and long-term reversibility; careful documentation and post-repair monitoring help ensure that repairs solve the underlying movement and do not inadvertently accelerate other failure modes. This technical approach to crack repair transitions to broader stabilization strategies for rubble stone and severely deteriorated foundations.

How Do You Stabilize Rubble Stone and Brick Foundations Without Damaging Historic Value?

Stabilizing rubble stone and historic brick foundations favors localized, concealed methods that restore bearing and continuity without wholesale replacement of original fabric, thereby preserving historic character. Techniques include grout or lime-based injection to fill voids in rubble foundations, localized underpinning beneath failing sections, and hidden reinforcements such as stainless steel pins or carbon fiber strips that are installed within mortar joints or behind finishes to minimize visual impact. Full replacement is a last resort; whenever possible, conservators recommend consolidation of existing masonry, compatible repointing, and targeted structural support that can be reversed or removed without extensive loss. Clear documentation before and after stabilization, combined with a monitoring plan, preserves both structural safety and the historical record, and it prepares the site for any required coordination with preservation authorities.

How Do You Prevent Water Damage and Mold in Historic Maryland Basements?

Key prevention steps homeowners can take:

- Correct grading and downspout discharge: Ensure surface water flows away from the foundation to reduce hydrostatic load.

- Maintain gutters and leaders: Clear gutters seasonally to prevent overflow and concentrated runoff that soaks foundation soils.

- Install interior drainage and sump systems where needed: Manage infiltrating water without altering exterior historic fabric.

Implementing these prevention measures significantly reduces the frequency and severity of water events, and the next table compares moisture-control solutions by effectiveness and maintenance needs to help owners prioritize investments.

Comparing moisture-control solutions for historic basements:

| Solution | Effectiveness | Maintenance/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dehumidifier | Controls RH effectively in enclosed basements | Requires electricity and periodic maintenance; sizing matters |

| Crawl space encapsulation | Reduces ground moisture and improves air quality | Must be used cautiously to avoid trapping moisture in historic assemblies |

| Landscape grading and gutters | Prevents water accumulation at foundation | Low maintenance if properly executed; first line of defense |

These moisture-control strategies, combined with routine monitoring, help preserve historic finishes and structural materials by minimizing the conditions that promote mold and masonry decay.

What Are Best Practices for Mold Remediation and Dehumidification in Older Homes?

Mold remediation in historic basements begins with a thorough assessment to identify sources—active leaks, high ground moisture, or condensation—and then uses the least destructive cleaning and containment methods to protect original materials. Best practices include isolating the affected zone, using localized removal or cleaning with gentle mechanical action, applying appropriate antimicrobial treatments only where necessary, and avoiding sandblasting or aggressive chemical stripping that can damage historic surfaces. Dehumidification should be sized to basement volume and set to maintain relative humidity under roughly 60% to inhibit mold growth, with continuous monitoring and placement that avoids directing airflow across fragile finishes. Post-remediation, owners should address root causes—grading, drainage, or faulty plumbing—so that remediation is not a temporary fix but part of an integrated moisture-control plan that sustains preservation outcomes.

How Does Crawl Space Encapsulation Benefit Historic Maryland Properties?

Crawl space encapsulation can reduce ground moisture migrating into building assemblies, improve indoor air quality, and lower humidity-related decay risks, but it must be applied judiciously for historic buildings where breathability matters. Encapsulation involves installing vapor barriers, improving perimeter drainage, and sometimes adding conditioned air or dehumidification to the crawl space; these measures directly reduce vapor drive into floor structures and reduce wood rot risks. However, if encapsulation traps moisture in masonry or prevents needed drying, it can inadvertently concentrate salts and lead to long-term damage, so professionals typically recommend a tailored approach based on moisture mapping and hygrothermal analysis. When appropriate, encapsulation paired with monitored ventilation and maintenance can be a valuable part of a preservation-minded moisture strategy that protects finishes and structural timbers while respecting the building’s original construction.