One arrives at Nithurst Farm along a country road through a band of trees to discover the house at the bottom of a straight, steeply sloping drive. It is located in the middle of a field surrounded by further bands of thick trees, which seem to stretch to ridges of the South Downs in the distance, effectively hiding most buildings for miles around and giving the site – formerly occupied by a 19th-century farm worker’s cottage – a sequestered, isolated feel.

The architect, Adam Richards, and his wife and three young children had been renting the cottage for five years when the opportunity arose to buy it. ‘It was small, dark and cold,’ he recalls, ‘structurally unsound and with very low ceilings. But we thought carefully about extending and adapting it.’ In the event, its narrow domestic curtilage meant it couldn’t be extended east or west, while any extension to the north or south would have resulted in tortuous internal circulation. Considering also the spatial and planning issues that insulating the structure would create, Richards decided to demolish, recycling the rubble into garden walls and retaining the roof tiles for future use. ‘In making the decision to demolish,’ he says, ‘we were conscious that the replacement house should be built to last.’

Certainly the new house, which, with its seven bedrooms, can no longer reasonably be termed a cottage, has a look of weighty permanence. From afar, its stacked, tripartite silhouette has an almost ecclesiastical air, like an isolated country church, its brick-clad volumes also recalling the abstracted geometries of Arthur Shoosmith’s Garrison Church in New Delhi, or some industrial engine house.

And, like a church, this is not a building designed to merge into the landscape. Its sit-up-and-beg mottled brick form, graphic yet soft against the green, has a prominence and strange sense of grandeur to it. It is punctured by over-scaled arches stacked at three levels in studiedly random slippage above each other, the upper ones half-submerged, like giant fanlights. There is a repetitive boldness to these, vaguely suggestive of some unbuilt Valerio Olgiati project. Indeed, a host of architectural echoes flood in when contemplating this house. Its half-awkward, close-coupled stacked mass, playing tricks with scale, has something of FAT’s House for Essex about it, yet equally something of a fragment of Roman aqueduct. Richards describes the design as ‘treading a fine line between Modernism and Classicism’, also citing abstract geometric forms on a 1970s Robert Mangold print as an inspiration.

Here is a house consciously ‘doing’ architecture in a deeply personal, idiosyncratic way. Its fragmentary grandeur and concentrated layering of ideas is akin in sensibility to a folly. Indeed, it was to two local follies – on the nearby Petworth and Pitshill estates – that Richards made reference as precedents in his planning application. Planning was dealt with by the South Downs National Park (SDNP) authority rather than via the local authority, Chichester District Council, which Richards recalls as having been advantageous. ‘My experience has been that the park’s planners are more receptive to good contemporary design than those at the local district council,’ he says. ‘The SDNP’s design guidelines place emphasis on recognising local distinctiveness. We were able to draw on two nearby folly towers as design inspiration, as well as local buildings that incorporate large brick arches.’

Richards describes the design as ‘treading a fine line between Modernism and Classicism’

The house’s envelope is formed of an in-situ concrete inner layer with an outer brick skin. While other structural systems were considered, including cross-laminated timber for the inner-layer, only concrete gave the structural stability or longevity required in such economic form – budget-wise or volumetrically. ‘It means the house has a design life of at least 500 years,’ he says. Clearly this is a project playing the long game. With whole-life carbon calculations potentially over half a millennium, the environmental focus is weighted to long-term operational carbon emission savings from its highly insulated envelope and exposed thermal mass, rather than in minimising embodied carbon per se. But the concrete used is lean – a low-cement 50 per cent GGBS mix – cast as thinly as possible to reduce volume, its exposed finish dispensing with the need for any lining material and offering long years of low maintenance.

Aesthetics did come into it, of course, with Richards clearly enjoying the concept of ‘an industrial ruin wrapped in a Classical ruin’ suggested by the concrete/brick double skin, while admitting too that he’s loved raw concrete interiors ever since first seeing pictures of a Tadao Ando house. The concrete finish, while perhaps not up to Japanese standards, is fine enough. In any case, its rough-around-the-edges quality feels appropriate in this rural setting, even forgivable given the logistics of pumping concrete on site. Richards points out and clearly enjoys ‘areas of imperfection’ caused from days when the pump got blocked. To save costs and main contractors prelims, the concrete, drainage and groundworks packages were let by direct contract, with the other packages then tendered separately. The build was a two-stage process, with a five-month pause in construction over one winter, the concrete structure left sitting and exposed to the weather. This was the result of difficulties co-ordinating two contractors, the need to raise further funds and the wait for suitable weather for lime mortar work to cure, meaning the project was over two years on site.

Up close, the house, which is orientated north-south on its long axis, looms much larger than expected. Plays of scale continue with 30mm lime-mortar joints making the bricks look shrunken while giving a looser, softer feel to the masonry façades. They also practically allow for extra movement of the brick skin against the inner concrete box without the need for movement joints.

The mix of colours of the two bricks employed – a reddish Wienerberger and greyer Ibstock old English bluff – is played with too, creating stylised patterns. Richards describes these as ‘motion blur’; they look like smears to one side of the windows, reminiscent of mud splashes on a car’s wheel-arches or the stylised go-faster flame graphics on a hot rod.

Similarly on the south side, where the house rears up to three storeys, lines of grey brick create a double-criss-crossed grid between the more orthogonal window openings, as though ready for a game of noughts and crosses or like a giant hashtag – ‘We were thinking of calling it Hashtag House at one point,’ says Richards with a smile. The shape again had its origins in a picture: Mansions of the Dead, a 1932 drawing by Paul Nash, which shows a floating, gridded structure.

This brick patterning sounds somewhat jokey and crudely literal, but it’s subtly achieved, not feeling like a succession of set-piece one-liner references. It is typical of the level of experiential incident and detail of this house which serves to underline what a labour of love it has been.

A further sense of frozen movement is underlined by the house’s long flank walls being canted at slight angles towards each other. This means the house is essentially coffin-shaped in plan, with its main entrance sited in one of two chamfered corners at its northern end, leading off a loosely corralled yard formed by the existing outbuildings to the north-west. You enter a small entrance lobby/porch with a short stair leading up. This space is almost perversely tight, but pleasurably so in contrast to the release out into the lofty room at the stair head, a 4m-high room which takes up the majority of the ground floor. This spatial sequence, juxtaposing small against big, structures the whole house, with large light spaces often emphasised and contrasted with tight darker spaces and circulation areas.

This large room is essentially a classic kitchen/diner ‘family’ room circling a built-in island unit, yet on a scale and with a complex spatial play that shifts it into something grander, akin to a Medieval/Arts-and-Crafts-type hall. This is underlined by a mezzanine stair landing at its south end, being expressed theatrically like a minstrels’ gallery. At the north end, steps lead up to a more informal living/play space elevated slightly and separated off by a half-height fitted sideboard-cum-wall. The main body of space feels slightly ecclesiastical again, its side walls corrugated with apses set between ‘towers’ of concrete. These variously contain WC, utility, larder, study and stair in small dark poché spaces. The spatial qualities of the interior are once more generated by a palimpsest of architectural and other references. Richards mentions Hermann Muthesius’s Das Englische Haus, Palladio and Tarkovsky in one breath. Indeed, the latter’s film Stalker, which consists of the journey to a room in which all desires are met, formed a fairly literal visual blueprint for this house – in what for Richards one feels is both knowing in-joke and deeply-felt home truth.

Tarkovsky’s film Stalker, about the journey to a room in which all desires are met, formed a visual blueprint for this house

The angled side walls of the plan imperceptibly funnel this main room’s orientation towards an alcove under the mezzanine balcony to the south, the spatial flow focused nicely on axis on to a print of a particle accelerator. The symmetrical axis is then blocked à la Lutyens by a wall, which then takes you off to the sides. There’s the main stair to the right, while to the left a darker passage leads to steps up into a near-Classically proportioned, light-flooded sitting room, with vertical almost Regency-like French doors, facing due south, and an open fire on the north wall. Richards refers to this as a ‘solar’, a literal warming room in the Medieval sense. It’s clearly the adult ‘formal’ end of the house and the one space that feels positively connected out to the garden.

Upstairs, the first floor of bedrooms is arranged fairly regularly, with stud-walls for future flexibility. Its main idiosyncrasy is the couple of ensuite bathrooms that occupy the upper mezzanine level within two concrete ‘towers’ in the kitchen/hall and are accessed down tightly-turned flights of steps. Meanwhile, axial symmetry here wins through in a stair leading precipitously up to the light – heavenward even – of the second floor. This forms the ‘tower’ at the south end, where twin light-filled master bedrooms sit akin to high loggias.

This is an oneiric house – as any house inspired by Paul Nash and Tarkofsky inevitably should be – at times indulgent, at times nicely sober, awkward and charming, clever but perverse. Richards and his wife have unashamedly poured their dreams – and what their budget would allow – into it. Intended for the long haul of family life, indeed built to last a notional 500 years, its focus on the sunlit uplands of the future makes it feel slightly unworldly; out of sync as a contemporary home.

It is embedded in the countryside while inside feeling oddly removed from it – although this is almost refreshing after so many interiors blanded out by inside/outside walls of glass. Indeed it has qualities of shadow and gloom that are rare these days – but this is a characteristic to prize. This and the oddities of the plan, reminiscent more of an ancient house, give the sense of a house with old bones.

This is a project focused on the deep past and the far future. While it does the necessaries in terms of environmental performance, one has the sense that this was not the driver here; its eyes are on the traditional sustainability prize of putting down roots for the long term. One just wonders, with the climate emergency upon us, whether a focus over 500 years and not the next decades can still be justified.

Architect’s view

To justify demolishing the existing building on such a sensitive site we felt it important to design a new building that would last for 500-plus years, We looked at a range of structural options to deliver this and which had to work with the brick outer layer for which we had planning consent, considering CLT, steel, blockwork and internal brickwork but discounting them for structural, longevity and cost reasons.

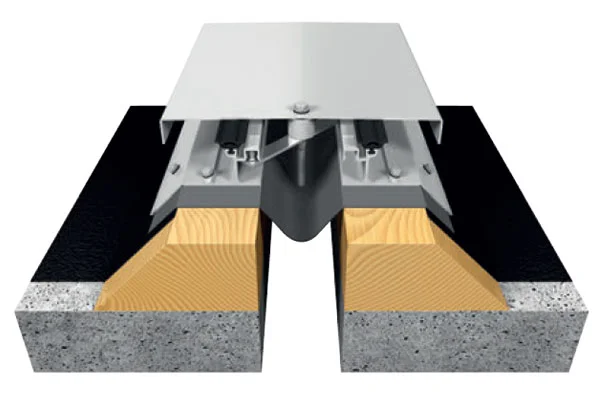

Choosing concrete enabled us to structurally support the brickwork efficiently over the full height of the building. The top-floor exterior brickwork is hung from a steel angle fixed to the concrete inner shell. This saved us a full-height half-brick layer in the external wall build up, while concrete gave us slim wall thicknesses of 175mm, maximising usable internal floor area.

To make the concrete more sustainable, we chose to incorporate 50 per cent ground granulated blast furnace slag. Leaving it exposed internally enabled us to save on finishes – no plaster or paint – while the thermal mass this provided means little energy is required to keep the house heated as it is very temperature stable.

‘Haptically’, concrete is ‘real stuff’, which exudes a sense of materiality, and aesthetically it tied in with our narrative relating to Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker, which was instrumental in presenting the ruins of industrial society as things of beauty.

After the initial aim of using a ground-source heat pump proved unfeasible (upgrading the electrical supply to three-phase pushed the heating kit budget over £100,000), a two-stage strategy was devised: the house’s insulation was increased and the existing LPG tank re-used. The plant room was moved to an outbuilding big enough for a biomass boiler to be installed after the LPG boiler reaches the end of its life.

Adam Richards

Engineer’s view

The structural approach was one of simplicity and robustness; this is a building built to last. An internally exposed concrete core is founded on strip footings and provides all the major structural functions of transferring vertical and horizontal loads and providing support to the external brickwork.

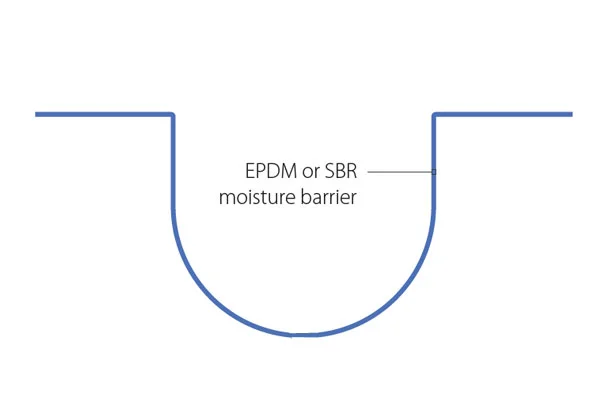

The high carbon content associated with reinforced concrete construction was mitigated by using 50 per cent GGBS as a cement substitute, by reusing formwork and specifying recycled aggregate, and ultimately by avoiding the need for additional internal finishes. The core is separated from the strip footings to avoid a thermal bridge.

Working within the constraints of the budget, an early decision was made to embrace the concrete in its raw state and accept the inevitable imperfections in the finished surface. Nevertheless, care was taken to ensure consistent workmanship and to avoid the need for repairs and signs of ‘mistakes’. This extended to specifying the location of construction joints and the setting-out of board joints.

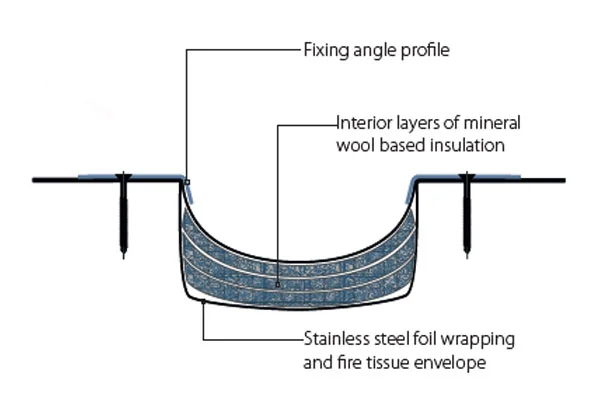

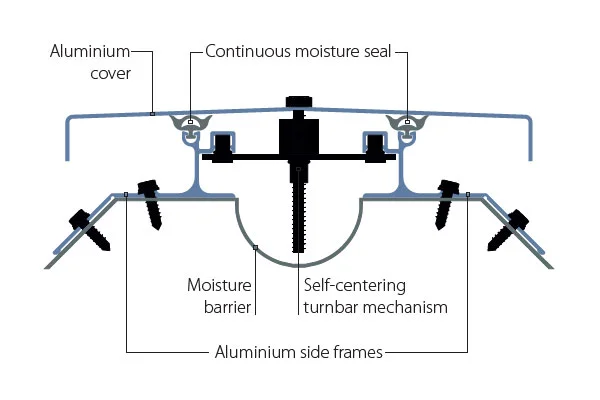

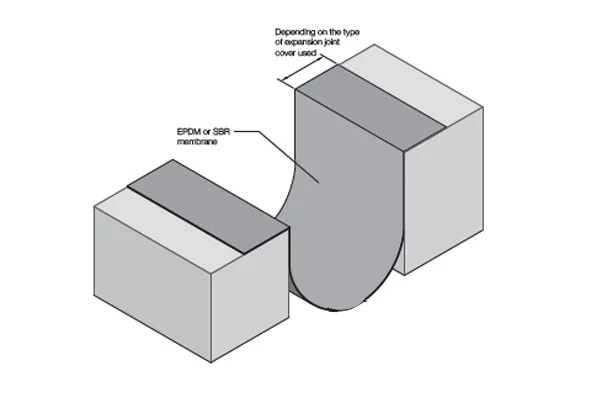

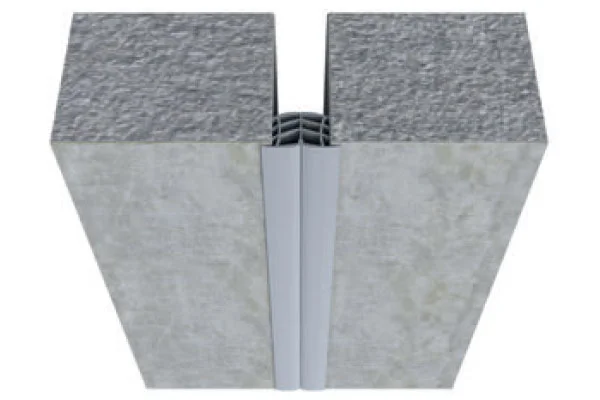

The brickwork employs thick mortar joints, round arches and a stepped elevation and section. In addition, the brief called for an absence of horizontal movement joints, which would normally be used to address the potential for masonry cracking following drying shrinkage or thermal expansion and contraction. By employing traditional lime mortar, stainless steel bed-joint reinforcement and horizontal slip planes at the masonry steps, this aim was realised.

Peter Laidler, director, Structure Workshop

Working detail

Nithurst Farm is designed for a 500-plus-year life. This led us to the use of robust and durable materials: the house is conceived as a modern concrete house wrapped in a Roman ruin with structural brick arched openings. We wanted to highlight this theme of deliberate anachronism by emphasising the separate qualities of the brick outer skin and the concrete inner one. We have placed the glazing in the concrete zone, allowing the backs of the brick arches to be visible from inside. This gives the brick outer layer an autonomous quality, while registering the presence of the well-insulated cavity. To achieve this, the brick layer thickens up around the windows, and the outward thrust of the rear part of the arches is taken by thermally separated steel angles bolted back to the concrete.

We used 30mm lime mortar joints in the stepped brickwork to emphasise the building’s weight and sculptural form. This enabled us to eschew movement joints, and improved the overall appearance of the bricks. It also plays a visual game of scale. Wall ties fix back to vertical stainless-steel slots cast into the concrete. Darker bricks are used running north from the arched windows, based on ‘motion-blur’ in cartoons. This helps create the uncanny sense of a heavy building that seems somehow ‘on the move’.

Concrete is left exposed for internal walls and ceilings; services are distributed under the floors. Surface variety and imperfection in the concrete is celebrated.

Adam Richards

Project data

Start on site January 2017

Completion February 2019

Gross internal floor area 397m2

Construction cost Confidential

Construction cost per m2 Confidential

Architect Adam Richards Architects

Client Jessica and Adam Richards

Structural engineer Structure Workshop

M&E consultant P3r Engineers

Quantity surveyor MPA Associates

CDM co-ordinator Head Projects

Approved building inspector Head Projects

Main contractor Garsden Pepper

Concrete contractor SMD Formwork

CAD software used Vectorworks

Annual CO2 emissions 16.79kg/m2 (predicted)

Draining design Benton Design Consultancy

Lighting design Lightplan Lighting Design

Performance data

On-site energy generation None

Heating and hot water load 28,928 kWh/m²/yr

Total energy load 149.76 kWh/m²/yr

Predicted annual carbon emissions 16.79 kg/m²

Annual mains water consumption 45.6m³/occupant

Airtightness at 50pa 2m³/hr/m²

Overall thermal bridging heat transfer coefficient (Y-value) 0.15W/m²K

Overall area-weighted U-value 0.27 W/m²K

Embodied/whole-life carbon Data not available

Predicted design life in years 500-plus