READ MORE

Life on the San Andreas: A 4-part series

This is a 4-part series on life in Parkfield, California, the science of its seismology, and its distinction as “Earthquake Capital of the World.”

Forty minutes northeast of Paso Robles lies a tiny ranching town whose reputation far exceeds its size.

Most visitors reach the town from the southeast, along a worn, two-lane road that follows Cholame Creek through the grassy Cholame Valley.

Unbeknownst to many who drive it, this lonely yet peaceful valley-bottom stretch of road parallels and at times zig-zags over the San Andreas Fault.

Like a red carpet, the world’s most famous fault line leads travelers straight into Parkfield, California — the “Earthquake Capital of the World.”

The 18-resident town is known by scientists and the public alike for its shaky history, thanks to its proximity to the fault. Since 1857, this section of the San Andreas has produced seven strong earthquakes, one striking every couple of decades.

The remarkably consistent pattern has fascinated scientists since it was first recognized decades ago. In the ensuing years, seismologists from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and other institutions have flocked to Parkfield to study the fault and run countless experiments in the area.

Scientists, reporters and tourists alike pass through town, hoping to be there when the next one strikes.

All the while, the residents of Parkfield have gone about living their lives, in the shadow of the San Andreas.

An isolated ranching town

Parkfield’s quarter-mile-long main strip is home to a smattering of buildings, including the one-room elementary school, the USGS-Berkeley earthquake monitoring site, a Cal Fire station and the Parkfield Cafe and Lodge. A row of mismatched mailboxes outside the cafe serves the dozen or so homes located on a handful of dirt roads off the main street.

A blend of old rusting pickup trucks and newer SUVs and sedans kick up clouds of dust as they pass through town, some stopping at the cafe. The closest gas station is in San Miguel, nearly half an hour away. Parkfield has no grocery store.

“Parkfield’s community is definitely a ranching community,” said John Varian, the owner of the V6 Ranch and the town’s only inn and restaurant. Most residents work on the large ranches scattered throughout the valley.

The Varian family has helped turn this once-secluded valley into a tourist destination for city-dwellers seeking fresh air and open fields.

But they’ve also embraced their earthquake legacy.

Signs throughout the town that read “Earthquake Capital of the World” and “Be here when it happens” give Parkfield an obscure roadside attraction vibe on par with Carhenge or the world’s largest ball of twine.

However, a permanent USGS field office suggests that the town’s notoriety is no cheesy gimmick.

That fame reached its peak in 1992.

1992 quake puts Parkfield in the spotlight

On Oct. 19, 1992, a magnitude-4.7 earthquake struck just north of Parkfield, prompting the USGS to issue an alert that a magnitude-6.0 quake was possible over the next 72 hours.

Scientists had good reason to be concerned. A quake this size has struck near Parkfield about once every 22 years since 1857. Some of these quakes had been preceded by a sizable foreshock — a precursor earthquake — like the one on Oct. 19.

Prior to 1992, the last magnitude-6.0 earthquake near Parkfield had occurred in 1966 — 26 years earlier. It looked as though the fault was overdue.

Within hours of the alert, the media descended on the tiny ranching community. The town’s main street was lined with vans housing satellite dishes from major news outlets throughout the country, said Jack Varian, patriarch of the Varian family, which has lived in Parkfield for the last 60 years.

Not just reporters, but scientists, first responders and all manner of earthquake enthusiasts flooded into the town.

And for 72 hours, everyone waited for something big to happen.

“It was an earthquake in itself,” Varian said.

Reporters milled around talking to residents and hung out in the town’s only restaurant to drink and watch football, he said. “By the third day, they’d interviewed anybody and everything. They’d written every byline they could think of.”

The alert expired on Oct. 22 without incident. And Parkfield went right back to being the remote ranching town it was before.

“I’ll tell you, the 72nd hour, within 15 minutes this town was a ghost town,” Varian said.

The much anticipated quake did not occur until 12 years later.

Bridge into town crosses San Andreas

One of the clearest indications that the town exists by the will of the San Andreas is the Parkfield-Coalinga Bridge.

Visitors to Parkfield arrive at the south end of town by crossing the bridge over Cholame Creek, which connects Parkfield with vineyards and ranches to the west.

The bridge also connects the Pacific plate with the North American plate, on which Parkfield sits. Placards alert drivers to this fact and inform them that they are driving over the San Andreas, which runs through the creek.

The land west of the bridge is creeping one to two inches northward per year — about as fast as fingernails grow — relative to Parkfield.

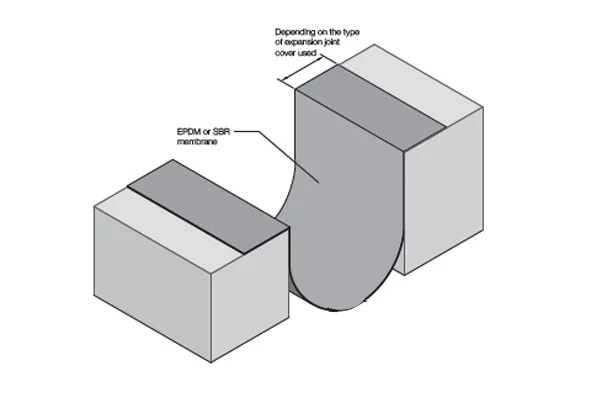

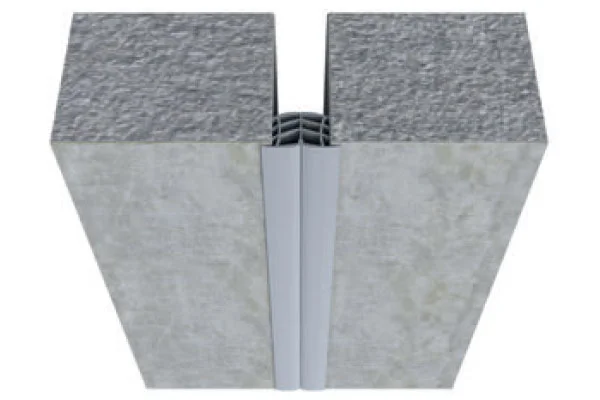

The slow-motion march along the San Andreas is visible in the curvature of Parkfield’s bridge. The guardrails are gently bent toward the north on the western side. To accommodate bending of the bridge, the expansion joint in it’s center is wedge-shaped.

Most of the time, this movement is imperceptible.

Cows roam the creek bed below, unknowingly grazing the boundary between two continent-sized land masses. But every couple of decades, the two sides of the fault suddenly slip past one another in a strong earthquake. With knowing foresight, the engineers who designed the bridge left room in its supports and rails for continued drift.

The cafe brings locals and tourists together

The Parkfield Cafe and nine-room lodge property across the street make up a large part of the town’s main drag. The lodge is an eclectic collection of buildings. One of the guest rooms occupies an old yellow water tower with the worn paint of a Shell gasoline advertisement brandished on its side. Another room is located in the town’s old post office.

Parkfield’s social center and only restaurant is the cafe, which is owned and operated by John Varian and his wife, Barb.

Inside the log cabin building, the walls are adorned with old tools and photographs. Hundreds of branding irons hang from the cafe ceiling.

Varian assures they are well secured. This is earthquake country after all.

A sign hung from a ceiling beam tells diners “If you feel a shake or a quake, get under the table and eat your steak.” The tongue-in-cheek motto is not far off from the advice of experts to drop, cover and hold on during an earthquake.

Cafe diners often include guests of the ranch and folks passing through town on car or motorcycle rides, said Ian Reeder-Thompson, a stone mason and computer programmer who does odd jobs on the Varians’ V6 Ranch, including moonlighting as a bartender in the cafe.

John Varian’s booming laugh and animated storytelling fills the restaurant. He often sits at one of the high top tables chatting with ranch guests and telling tales, Reeder-Thompson said.

“The locals come after dusk,” he noted.

Diners can pair a shakin’ style burger with a glass (or jug) of Parkfield-brand earthquake wine.

Outside is a shaded green lawn with home-built picnic tables and a Seussical tree house.

“We do everything in house,” Varian said, “partly because I’m cheap, partly because it’s really hard to get people to come out this far to work.”

Daily life on a dude ranch

Folks living in the earthquake capital of the world don’t spend their days dwelling on the town’s infamous reputation or the impending quake that is sure to rattle the area in the near future.

The Varians operate their 20,000-acre property as an Old West tourist getaway and welcome visitors for trail rides and other events Thursday through Sunday. The town’s isolation attracts folks seeking respite.

“It’s just peace and quiet,” John Varian said. “That’s what (visitors) like the most.”

This is particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, when people are looking to escape the confines of crowded cities.

“We’ve never been in the business to make Parkfield a big town,” Varian said. “Everybody out here wants it to stay just the way it is.”

After the tourists leave, things get even quieter.

“Come Monday morning, you can lay in the middle of that street for four or five hours and not get run over,” Varian said. “I love that,” he added with exuberance.

When the ranch isn’t hosting visitors, Varian and his crew spend their time maintaining the property. Ranch hands and interns do everything from cattle work to landscaping to laying brick. Also, there’s the never-ending list of repairs. “You have 100 miles of fence line, 50 miles of pipelines. I once added up … I had like 65 toilets,“ Varian said.

“Every single day is completely different,” the lifelong rancher said. And he wouldn’t have it any other way.

Scientists keep an eye on the San Andreas

Today, the town’s western heritage exists alongside its more recent earthquake fame, and that presence is noticeable right upon arrival to Parkfield.

Some of the first buildings encountered driving into town from the bridge are the USGS and Berkeley field stations.

The USGS field office is located in a modular trailer next to the UC Berkeley quake monitoring station — a windowless shipping container-sized building.

The Cholame Valley is scattered with equipment that measures how fast the plates are creeping past one another and how rocks are being deformed near the fault. The USGS maintains 18 permanent seismometers within 25 miles of Parkfield that listen for slight rumblings in the ground. These instruments detect hundreds of small earthquakes each year.

Parkfield used to have a big scientist presence. During a major prediction experiment started in the late 1980s to ‘90s — which ultimately failed to predict a quake — and a drilling project in the early 2000s, the region saw a flurry of attention.

“Not anymore,” said Jack Varian, John’s father.

The USGS field office has not been permanently staffed since its last keeper retired several years ago. Technology has evolved over the years. Many of the seismic instruments in the area can now be remotely monitored and are serviced only occasionally.

That doesn’t mean that Parkfield has been forgotten.

Earthquake tourism

USGS rearchers and byline-hungry reporters chasing a big story aren’t the only ones who relish in Parkfield’s regular strong temblors. Scientists from around the world make a pilgrimage to the fabled earthquake mecca.

“This place is kind of legendary,” seismologist Julian Lozos said. “I know earthquake scientists from other countries who go, ‘Oh, we’ve heard of Parkfield.’”

Lozos, a professor at Cal State Northridge, has been coming to the town since 2007. He made his first trip just to see the San Andreas, but he said he keeps coming back because he enjoys talking to the people and being in such a beautiful place. “Also, the food at the cafe is really good,” he said.

In the field next to the cafe, Parkfield hosts its annual bluegrass festival. Lozos plays fiddle and mandolin and has been coming to the four-day event since 2015.

During the long weekend, he runs tours of Parkfield’s earthquake history.

He takes festival-goers to the bridge and talks about how the San Andreas shapes the scenery around them. He said the locals have even started coming on the tours.

A landscape born of immense force

The Parkfield bridge is a tourist destination for some — a place to appreciate a force of nature quietly but tangibly exerting itself on the landscape.

The residents of Parkfield are all too familiar with how the San Andreas shapes not only the bridge, but the landscape around them. Some even marvel at it.

“It is the most uniquely beautiful terrain,” John Varian said. “You can go from a white rock, to a red jasper, to this blue serpentine rock and they’re like the sizes of houses,” the rancher admired. “They’re all right together and you’re like, ‘How did all of this get so mixed together?’”

The North American and Pacific plates have been sliding slowly past one another for the past 20 million years. Rocks that formed hundreds of miles apart are now juxtaposed across the San Andreas.

The greenery even grows better in the tree and shrub-lined creekbed than the surrounding golden fields in part because of the fault, Lozos said.

Groundwater can flow easily through the pore space within the sedimentary rocks that make up the Pacific plate in the area. When that water reaches the hard granite of the North American plate, it pools there and gives much-needed water to plants.

“Even in the droughtiest drought there’s still going to be a very, very narrow band of green there because of the groundwater hitting that barrier along the fault,” Lozos said.

“Most people would think of the San Andreas Fault as a hazard. It really is, in a kind of way, the landscape artist,” he said.

In some places, tens-of-miles-long bends in the fault line cause rocks on either side to be pushed together, giving rise to mountain chains such as the San Gabriels north of Los Angeles. In other places, the fault bends the opposite way, forming a depression. Cholame Valley, where Parkfield sits, is itself a trough brought about by a rightward step in the fault.

Varian knows this. “I mean, we’d be Kansas otherwise, right? I mean who wants to look like that? Ya know, the fault is what made California beautiful,” he said.

Earthquakes are part of life

The same force that formed California’s picturesque mountains and valleys is that which gives Parkfield notoriety as the Earthquake Capital of the World.

More than 700 earthquakes have been recorded in the Cholame Valley in the last 10 years, according to the USGS. Most of them struck in a narrow band along the San Andreas. Seven moderate quakes have jolted the region since 1857.

The regularity with which the San Andreas ruptures in a large earthquake here is unique to the Parkfield segment of the fault. Owing to its location between creeping and locked portions of the fault, the area is primed to fire off a strong temblor every couple of decades.

The last one was in 2004.

That means residents can expect another shock in the near future.

Few are so aware of Mother Nature’s proclivity for rumbling Parkfield as the town’s residents. But Jack and John Varian have come to accept what the San Andreas is capable of.

“For me, earthquakes are much ado about nothing,” Jack Varian said.

For John Varian, earthquakes “are interesting, but not scary.”

During the 2004 quake, he said he was driving a truck near his house and only noticed the shaking when he saw water splashing around in a nearby tank.

After checking on his family, he said he surveyed the damage to the structures on his property and found relatively little.

“Like all the earthquakes in Parkfield, everyone was fine,” Varian said.

After cleaning up from the quake, the town’s residents went right back to living their lives, still in the shadow of the fault.

“We’ve gotten a lot more out of the San Andreas than it’s taken, for sure,” he said.

Coming tomorrow: Scientists are studying the San Andreas to see how the fault’s regular creep affects our building and infrastructure at the surface. Plus, a look at California’s earthquake early-warning system.

This story was originally published September 1, 2021 at 5:00 AM.

Related Stories from San Luis Obispo Tribune

Jennifer Schmidt

The Tribune

Jen Schmidt is an AAAS Mass Media Fellow covering natural hazards and science news. She completed her Ph.D. in earth sciences at Lehigh University in 2018. She is an NSF-sponsored postdoctoral fellow at Temblor Inc., where she runs Temblor Earthquake News.