✕

As the technology for 3D printing with concrete-based materials has advanced in the last decade, many in construction have been waiting for some clear breakthrough to mark it as the next big thing. But the gains have been small and cumulative, with hundreds of homes built across the U.S. using 3D-printed structural concrete walls and other elements. Meanwhile, other markets around the world, where the demands for housing and urbanization are felt more acutely, are pushing the limits of 3D printer technology. Rather than seeing rapid adoption after any specific technological leap forward, 3D printing is on its way to being just another viable construction method, driven by wider availability and lower costs.

While the first victories for 3D-printed concrete in the U.S. have been in a few key areas, there are broader competitive advantages coming into focus. “We’ve entered a phase where homebuilders and developers seeking differentiation are embracing the technology,” says Bungane Mehlomakulu, senior director, building and construction science, at Austin, Texas-based 3D printing firm ICON. “It’s moved beyond novelty—builders now view it as a viable, permanent option, especially for resilient housing in disaster-prone areas.”

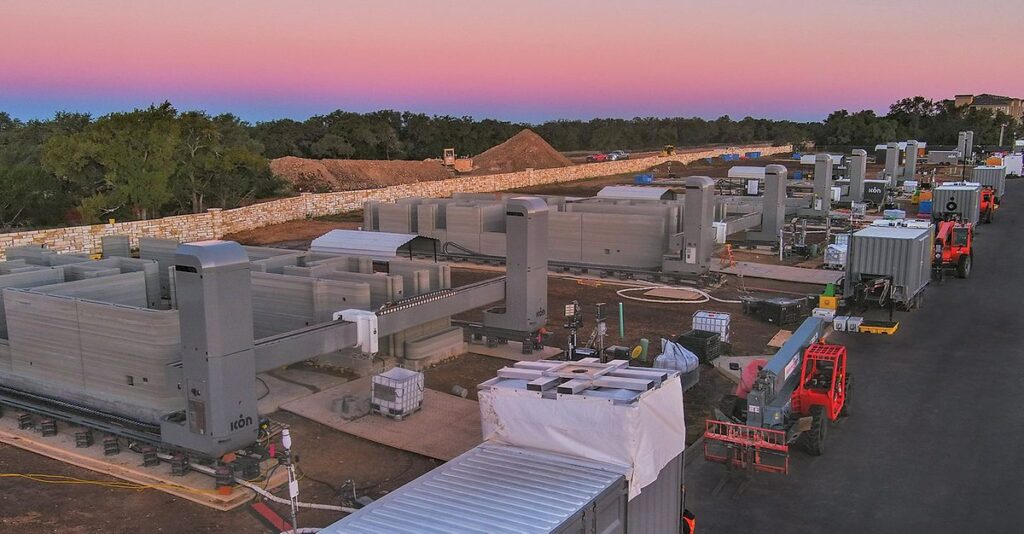

The Phoenix printer now in development by ICON has enough vertical reach for multistory concrete printing without needing to be repositioned.

Photo courtesy ICON

ICON itself has shown some resilience this year. One of the largest 3D-printing homebuilders in the U.S., the firm announced in January that it was laying off roughly 100 employees as part of a broader restructuring, while other 3D-printing startups that had raised significant funds in recent years saw similar cutbacks. But ICON has since repositioned itself and is expanding again, having recently grown beyond its home market in Texas to open an office in Florida, another hot spot for residential construction.

The firm is also planning for the longer term as it nears commercialization of its next-generation Phoenix printer, which is capable of working on multistory structures, according to Evan Jensen, ICON senior vice president of engineering. “The prototype [Phoenix] systems are in operation and the team is preparing for deployment to the field on full construction projects.”

Some developers choose to hide the distinctive ribbed look of 3D-printed concrete walls, while others wear it as a badge of pride.

Photo courtesy Icon

Photo courtesy ICON

The Phoenix printer uses a robotic arm that is a mix of an industrial robot and a concrete boom, which allows for more elaborate and taller prints than ICON’s current single-story, gantry-based printer systems.

One of the major objections when 3D-printed concrete first came onto the scene over a decade ago was the lack of applicable building codes and standards, which gave some engineers and building inspectors pause. But that knowledge gap has closed significantly in recent years. The International Codes Council published its Acceptance Criteria 509 (AC509) in 2022, and that has increased industry confidence in evaluating 3D-printed structural walls as monolithic concrete structures rather than some entirely novel concept.

“We’re not just doing one-off demos any more—real production is happening.”

—Zachary Mannheimer, CEO, Alquist 3D

“ICON has obtained an Engineering Service Report under AC509 for our printed wall systems, demonstrating a third party assessed and validated method of code compliance,” says Mehlomakulu, adding that the firm is continuing to work with ICC on the next code updates. But while firms like ICON are eager to prove their work is sound, they don’t shy away from collaborating with regulatory bodies. “While regulation in construction tends to lag with long adoption cycles, any multistory structures created with 3D printing should be undertaken in collaboration with state and local regulators to ensure public safety and build confidence in the technology,” he adds.

Much of ICON’s most visible work has been in the greater Austin area, with 100 3D-printed homes in the suburb of Georgetown almost all sold, and an ongoing effort underway to print 121 homes for Mobile Loaves & Fishes’ Community First! Village in Austin for the chronically homeless, says Jensen. At this point the main limiting factor is where ICON’s printers can travel to meet the demands of clients.

Taking in the amount of demand the company is seeing, Mehlomakulu says the 3D-printed construction sector is at an inflection point. “ICON is transitioning from being the sole user of our technology to a technology provider with our new suite of robotic printers, which will enable much wider adoption across more homebuilding markets.”

ICON has an in-house design-build group that can deliver projects from start to finish, but Mehlomakulu says that traditional designers and engineers are intrigued by what the technology makes possible. “Even basic elements like curved walls and corners aren’t typical in conventional construction due to the complexities of conforming materials like sheathing, drywall or stone to curved surfaces,” he explains. “There’s an entirely different approach to architectural thinking and possibilities with 3D construction, and we see a range of creative approaches from different architects and design professionals.”

Photo courtesy Alquist

Photo by Tyler Morgan

Alquist 3D is one of several firms taking 3D printing into the nonresidential sector, offering services that are faster and even cost-competitive with more established concrete construction methods.

3D Printing a Walmart

While there is a shortage of housing stock in the U.S., there is a vast world of public and commercial construction where 3D concrete printing is also making inroads. Alquist 3D, based in Greeley, Colo., has done its share of houses, but recently made waves in the nonresidential sector with some 3D concrete printing for Walmart. The projects themselves were small expansions, adding 5,000-sq-ft customer pickup facilities to a Walmart Supercenter in Owens Cross Roads, Ala., but they exhibit many of the qualities that could make 3D printing competitive in commercial construction.

“That [Walmart] project took us seven print days, which if it had been done with typical CMU block [it] would have been over 20 days, and that crew would not work in rain or snow, while we did so just fine,” says Zachary Mannheimer, Alquist 3D founder. The crew consisted of five robot printers and two workers. “With this project we were finally able to prove that 3D concrete printing is faster than CMU block,” he notes.

Tvasta is finding success in India’s booming housing sector. With a complete 3D-printing supply chain, the firm is equally able to print residential buildings or unusual planters for landscaping.

Photo courtesy Tvasta

Photo courtesy Tvasta

And while they were starting small, Mannheimer says the benefits were already evident. “One big reason Walmart chose to go with this was that scheduling a [traditional] crew would take months of lead time. 3D printing companies can come in and show we can do it faster, cheaper and more sustainably.”

Mannheimer says the biggest limiting factor is qualified operators. There are too many possible projects out there for any 3D printing firm to tackle them all. “If someone has a project somewhere, we need to send people there for the duration, but if there’s a local group [of trained workers] those costs just disappear.”

At a recent meeting with other 3D printing firms at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Washington, D.C., Mannheimer says there was a general understanding there was plenty of room for more firms, given all the work available. Alquist 3D is already working to educate the next generation of 3D concrete printing workers at the community college and even high school level.

The biggest issue is not the basics of running a printer or the “slicer” software that turns designs into instructions for the robot, but knowing how to troubleshoot problems when something goes awry on site. 3D printing requires the material to move continuously through the piping and out the nozzle, or it can seize up. It’s a bigger challenge than with existing concrete pumps, where slump characteristics can allow it to keep pumping even with inconsistent flow rates. Knowing how to resolve these kinds of onsite issues will be what allows general contractors and young people entering the industry to work on 3D printing concrete as a skilled trade, says Mannheimer.

Mannheimer says the hype cycle for 3D-printed concrete has come down from the heady “print a house in a day” claims of a decade ago, but the industry has matured significantly from those early times. “We’re not just doing one-off demos anymore: Real production is happening,” he says. “But the [concrete 3D printing] industry is still nascent, and still small at a global scale. But things are accelerating, and we expect a lot of growth in the next two to three years.”

`

Going Full 3D in India

As 3D printing’s practical limitations are being overcome, some companies are going for full vertical integration to control costs. This is particularly attractive in a market like India, where 3D-printing startup builder Tvasta has a fully integrated supply and labor chain for its 3D-printed structures. This has allowed the firm to tackle large masterplanned communities as well as commercial and government projects. Tvasta has already built dozens of homes with hundreds more on the way, working with some of India’s largest real estate developers.

“If we want to make 3D printing accessible to people, we have to offer everything,” says Adithya Jain, Tvasta’s CEO and founder. “The challenge is going against supply chains that have been there for 100 years.” The rapid growth of India’s cities and the need for housing and office space are driving interest in Tvasta. The firm isn’t limiting itself to one type of printing, and is able to print walls and structures onsite or offsite, and is also working in architectural facades, concrete landscaping or whatever clients want.

“For us, the scoreboard is how many units can we deliver.”

—Ethan Wong, co-CEO, HiveASMBLD

“We are doing about 80 bus stops in Chennai at the moment—bus shelters are a staple for us right now,” explains Jain. But he adds that whether it’s bus shelters, standalone residential homes or office space, 3D printing allows for endless customization and variation on standard designs without any additional cost. “The big thing we bring with 3D is the nonlinear forms—we’re not restricted to rectilinear structures.” He cites one two-story building Tvasta printed in Chennai, India, which featured a traditional rectangular layout for one corner of the first story and a circular shape for the second. “No formwork can transition shapes like this.”

The rapid pace of urbanization in India has helped Tvasta challenge its own engineers and designers, as well to tackle new forms of construction. Jain says the firm has already developed concrete mixes and printing methods that work across India’s different climates, from the warm and humid south to the cooler, more temperate northern provinces.

Much of this flexibility is due to the firm’s vertical integration. Tvasta manufactures its own printers and nozzles, and produces its own concrete admixtures for its projects. It’s an “all-of the-above” approach, explains Kalyan Vaidyanathan, Tvasta’s CTO. Like many 3D printing firms, it also sees sustainability as a competitive advantage. “The target is to lower embodied carbon, to replace GGBS [ground granulated blast furnace slag] with other inert materials,” he says. “And on the operational side, we get better thermal R values overall, reducing the heating and cooling requirements of buildings. We’re conscious that concrete is often seen as the enemy of addressing climate change, but we want to be able to build without feeling like we’re a part of the problem.”

Taking the concept of automated concrete construction in a different direction, Australia-based FBR has a truck-mounted robot arm that can place concrete masonry units with a high accuracy based on preloaded 3D models.

Photo courtesy FBR

Photo courtesy FBR

Robotic Bricklaying as Printing?

Sometimes the principles of additive manufacturing can be applied to methods other than wet concrete extruded out of a nozzle. Perth, Australia-based FBR uses a robotic arm mounted on a vocational truck to accurately place CMUs with millimeter-precision instead of placing concrete. The lower labor costs and the ability for continuous operation has shown promise, and the firm is already looking to expand into the U.S. construction market.

“We were asking ourselves ‘how do we deal with the chaos of a construction site?’” recalls Mark Pivac, CEO and CTO of FBR. “Let’s have a robot come in like a skyhook—you don’t have to worry about what the ground is like if you have a boom long enough to reach.” The company’s dynamic stabilization technology lets the robot plant itself at the site and place the bricks precisely and accurately. “We’re measuring with a laser tracker thousands of times a second with a robotic arm that can reposition, so no matter how the boom is moving, the block or brick goes exactly where it needs to be.”

FBR’s approach currently takes three workers: one to run the robot, one to drive pallets of bricks to the robot, and a QA person to check that CMUs or bricks are placed correctly. There is still some manual work—the robot can’t place rebar or lintels yet—but in places where labor is scarce or expensive, Pivac is finding interest. “If you can reduce a task that takes weeks to a day, that’s a huge difference.” The firm has a few machines working in Western Australia, but is continuing to refine their process to get the most out of the robot, he says.

These humble two-story homes from HiveASMBLD use 3D-printed concrete for the first story with prefab and stick-built construction for the second story.

Images courtesy HiveASMBLD

Mix-and-Match Design

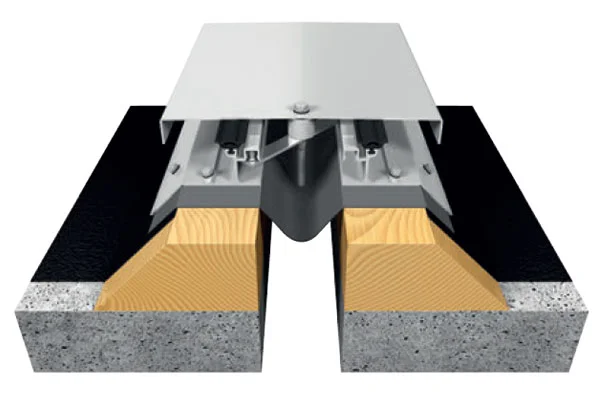

Ethan Wong was one of the earliest employees of ICON, but left in his first year to finish his engineering degree. He went on to co-found HiveASMBLD, a construction tech startup designing and building homes that are hybrids of 3D-printed concrete, prefabricated components and traditional methods. The typical building from the Houston-based startup can be seen in Zuri Gardens, a development it is undertaking with Cole Klein Builders. Its two-story homes will have 3D-printed walls for the first story and more traditional framing for the second story.

“The whole idea was to combine prefab components and 3D printing to create a whole system,” says Wong. “Instead of 3D printing the walls and then traditionally frame out the rest, let’s merge these ideas to create a new system from the ground up.” Wong notes that many 3D-printed concrete buildings run into scheduling slowdowns waiting on traditional fit outs from building trades to come in for the MEP and interior finishes. Modular prefabrication can address that, but prefabs often settle on box-like designs that can feel impersonal or even cheap. “We don’t want to just deliver a box,” he says. “What’s interesting about 3D printing is you can have all these interesting shapes and facades at no extra cost.”

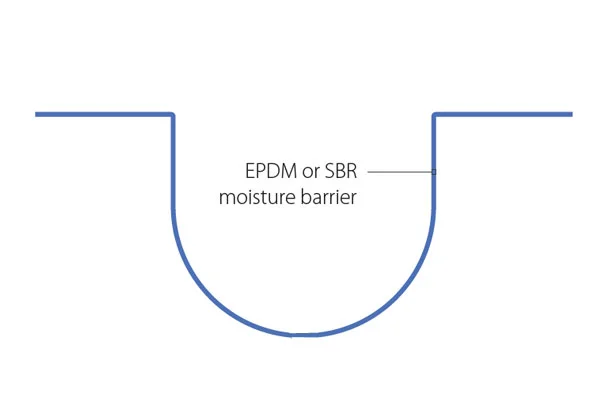

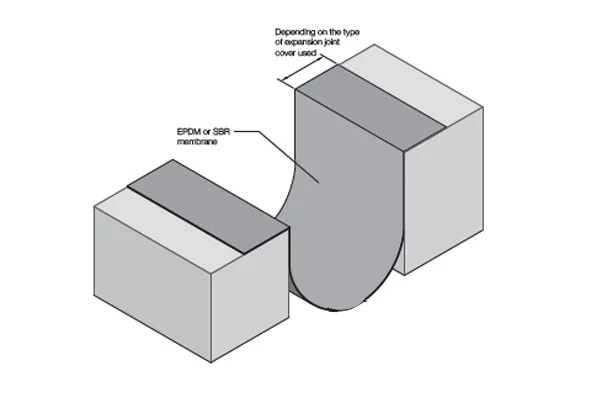

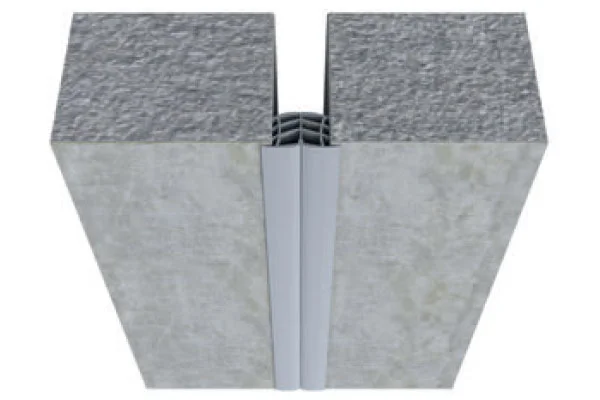

The Zuri Gardens development in Houston doesn’t go all the way with pure prefab and 3D printing, as it contains some traditional wood framing for the upper story. This led to the interesting challenge of preventing moisture from wicking into the wood from the concrete walls, a problem Wong’s team was able to address with small design tweaks. But even with the unexpected challenges of hybrid structures, they are seeing payoffs in schedule and cost. “For us, the scoreboard is how many units can we deliver,” explains Wong, who believes 3D printing should target affordable housing rather than putting up architecturally unusual luxury residences. “The interesting nut to crack is how to build 10 million houses, not $10-million houses.”

Rethinking Landscape Architecture in 3D

Most 3D printing companies work with in-house designers and engineers who are familiar with not only digital BIM tools but each firm’s custom slicer software that can take a typical design file and solve for how a 3D printer will build it on site. As a result, traditional architects have had to be a bit proactive to get into 3D printing. But that hasn’t intimidated Lindsey Heller, a licensed landscape architect and owner of Seattle-based design firm SKAPA.

“The momentum for [3D printing] has been really positive lately,” she says. “Our design files are printable, so I’ve been working with a lot of independent 3D printers and training crews on implementing them.” Heller has spent the last few years educating herself on 3D printing as well as teaching others, and finds herself becoming a resource and sounding board for others in the Pacific Northwest looking to try out 3D concrete printing. She’s fielded questions and done training sessions with architects, contractors and public agencies, and has even helped train up the union concrete masons of Seattle’s Local 538. “I tell architects, ‘you’re already working in Rhino [design software],’ so then I show them how little it changes their workflow to print out elements. They can do that today and price it out.”

In the Pacific Northwest, landscaping elements are also used for stormwater management, with Seattle building codes setting requirements for handling and retention. This has prompted Heller and her firm to use 3D printing to rethink basic concrete infrastructure elements. 3D printing not only allows for unusual shapes, but basic concrete objects such as planters and landscaping could have built-in voids for stormwater management and storage without structurally compromising them, or even visibly altering the exterior.

“It’s really amazing how easy onsite crews pick this up,” she says. While she doesn’t look down on those 3D printing more traditional buildings, she’s excited for what can be done with infrastructure and landscaping when designers push the limits of the technology. “You could print a big box store with a standard nozzle doing a 2-in. bead, but I’m seeking out all kinds of odd printer nozzles and tools for landscape 3D printing,” says Heller. “As this industry grows, people who have learned to do 3D printing will become masters of their craft, and it will be just another tool.”