Not so long ago, the waterfront of Seattle was bounded by the 2.2-mile double-decker Alaskan Way Viaduct, a gray monolith that dominated the landscape and separated the area from downtown. Now an aquarium, pedestrian bridges, parks and gathering spaces, colorful streets, public art and a rebuilt ferry terminal all mark the transformed waterfront—the result of approximately $1.2 billion and 20-plus projects in a program wrapping up this summer.

The redevelopment was made possible by the demolition of the viaduct in 2019, followed by the new tunnel that now carries traffic underground. “We completed our design sometime around 2018, and we had a couple of early projects that we were able to construct prior to the viaduct coming down,” says Angela Brady, head of the Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects and Sound Transit director.

Those early works included utility relocations and a reconstructed Pier 62.

Projects such as the new Overlook Walk offer amenities, green space and sweeping views.

Photo courtesy of the Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects

“It took around nine months to get the viaduct down, and we were able to start construction of our new waterfront sometime in the fall of 2019,” Brady says. “We’ve been under construction ever since. We have about 25 projects that the city has built to the tune of $1.2 billion.”

The program includes a park promenade along the water, a new surface street along Alaskan Way, rebuilding Pier 58, building an elevated connection from Pike Place Market to the waterfront and improving east-west connections between downtown and Elliott Bay. It is anchored by the $160-million, two-level Ocean Pavilion—designed by LMN Architects with a rooftop public park—that sits on a 38,000-sq-ft strip of city land in the old Alaskan Way right-of-way and features a new aquarium (ENR 12/25/23 p. 16).

Hoffman Construction Co. last year completed the approximately $68-million Overlook pedestrian walkway that connects the aquarium and Pikes Peak Market to the city core. “On the water side, it ties into the aquarium built by Turner; we had complex coordination between the two projects,” says Dave Johnson, Hoffman executive vice president. “We had two tower cranes swinging and overlapping. We had the new Alaska Way being built by [Gary Merlino Construction] underneath our bridge connector. We were sharing limited laydown and staging space while redirecting the public around intense construction.”

“The result is a really inviting and very comfortable parklike atmosphere.”

—Paul Huston, Program Manager, HNTB

There have been some bumps along the way. Pacific Pile & Marine, which has a $34.5-million contract to rebuild Pier 58, alleges in court that the city failed to pay for a request to speed up work on the pier. During demolition of the pier in 2020, several workers fell into the water along with slabs of concrete and heavy machinery. The workers avoided serious injury but sued the city for negligence.

Still, the city anticipates a celebratory completion on Sept. 6, with a promenade along Elliott Bay featuring artworks, foliage and a bike path. “Before the program began and the viaduct was in place, most of this area was roadway, the viaduct and its parking areas,” says Paul Huston, program manager with HNTB, which with joint-venture partner Jacobs provided construction services and program management for 12 projects.

“The program is adding over 15 acres of green space,” he says. “They’ve carefully and specifically chosen types of trees and types of flowers and plantings integrated throughout all of the additional artwork and the promenade planting materials that have a connection to the area, the Native American communities and to people who live and work here at the waterfront. The result is a really inviting and very comfortable parklike atmosphere that’s greener than it ever was.”

New waterfront features ample artwork, park spaces and family-friendly amenities.

Photo courtesy of Hoffman Construction

Building Up

While tunneling by the “Bertha” boring machine for the Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement received the most attention, the backbone for the waterfront redevelopment is out of public view.

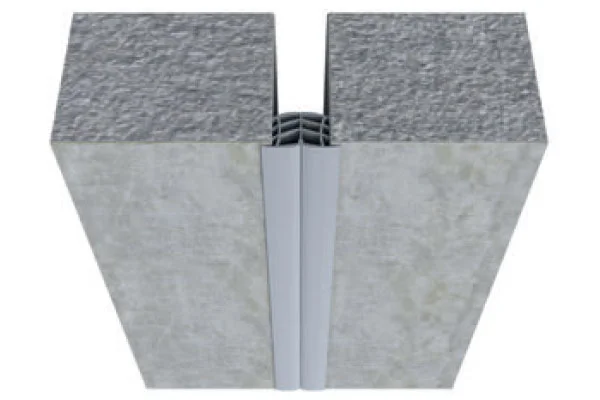

“The waterfront [program] actually started back in 2013 with the construction of the new seawall,” says Jody Robinson, construction management joint-venture manager with HNTB/Jacobs. “The old, aging seawall was wood, and the timber piles were built back in the 1910s.” The new seawall consists of more than 6,500 jet grout columns running for a mile under the new waterfront.

“We took the existing seawall and we moved it back 11 to 13 feet in order to reclaim [fish] habitat,” says Robinson. “Fish do not like the dark, so we created an additional habitat with light-penetrating sidewalk glass blocks. So now the fish go under there, whereas they never traveled under all these [old] piers.”

The Washington State Dept. of Transportation is one of the city’s many partners in the waterfront development. WSDOT handled the oversight and portion of funding for the Marion Street pedestrian bridge connecting the Colman Dock to the waterfront and the plazas and pedestrian areas around it, says spokesperson Steve Peer. “The waterfront project is a highly complex and technically challenging project, and the development of a consensus would not have been possible without the strong partnership developed between the leaders within both the state and the city agencies.”

Peer says the “projects have transformed the front porch of the city, creating a much more welcoming space for residents and visitors.”

Foam blocks helped crews build the complex angles of Overlook bridge.

Photo courtesy of Waterfront Seattle

Completed projects include:

A 17-block new surface street with connections to park spaces, the promenade and amenities, with raised street crossings, bike lanes and widened sidewalks, some 500 trees, extensive landscaping and green stormwater infrastructure.

A pedestrian-only street next to the Pike Place Market, with cherry trees and protected bike lanes with buffers that feature a pattern of wave designs that morph from rounded, water-like shapes toward the west to more mountain-like peaks to the east.

The Union Street Pedestrian Bridge, which navigates a steep bluff and serves as one of the many new connectors to the urban core. The bridge, which opened in 2022, features a concrete staircase, accessible elevator, elevated walkway and artwork.

The Marion Street Pedestrian Bridge, a concrete bridge with an arched main span and V-shaped columns that connects to the Seattle Multimodal Terminal at Colman Dock and Pier 48 water passenger services.

“The partnerships among stakeholders … were highly valuable.”

—Dana Warr, Spokesperson, Washington State Ferries

Pier 62, rebuilt to house a park, artwork and amenities for public events. The pier reconstruction included 175 steel piles and 214 new concrete deck panels, supporting nearly 40,000 sq ft of park space.

Pier 58, creating a public park that hosts a marine-themed children’s playground.

60,000 sq ft of new elevated park space, with seating, play areas and a concessionaire space featuring small local businesses. The pathway features landscapes, native plants and artwork reflecting the history of indigenous tribes.

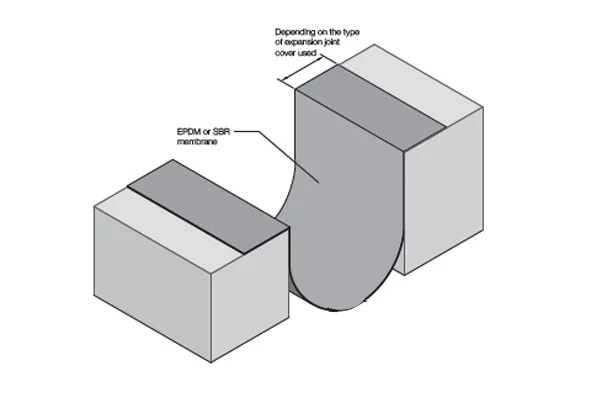

Hoffman’s Johnson notes that the bridge portion required “a lot of 3D modeling. It was a fairly complex structure with architecturally sensitive radii and features to make it more than a pedestrian bridge.”

Crews utilized prefabricated foam formwork sections to create the complex radius curves that make up the fascia on the north and south beams of the bridge, Johnson says. “Ninety unique foam form sections were created to form the 700 linear feet of fascia for those beams.”

Transformed waterfront features new connections to city neighborhoods and attractions such as Pike Place Market.

Photo courtesy of Waterfront Seattle

Big and Small

Hoffman is also wrapping up a $360-million rebuild of the ferry terminal at Colman Dock for the Washington State Ferries, which serves some 10 million passengers a year, in a contract with the Washington State Ferries. “We were dealing with fish windows to install 475 new piles and replace large portions of the trestle. On top of the trestle, we were completely removing the terminal building, replacing it in three phases,” Johnson says.

The Washington State Ferries coordinated current and future vehicle, bicycle and pedestrian flows to ensure seamless connections with the new waterfront reconfiguration and collaborated with the city on the design of the dock and terminal building to align with the new seawall and pedestrian bridge.

During the process, the Colman Dock design evolved to incorporate the city’s vision to connect people to the waterfront and encourage walk-on ridership as people visit the revitalized waterfront, says spokesperson Dana Warr, adding that “the partnerships among stakeholders during the creation of the new Seattle waterfront were highly valuable.”

The Port of Seattle shares the city’s mission: “The public should have access to our piers and shoreline,” says Toshiko Hasegawa, its commission president. The port contributed nearly $300 million in the most recent effort. “We have worked every step of the way to balance the needs of our working waterfront—which include trade, commerce, fishing and shipbuilding—with tourism, recreation and community experiences that draw so many residents and visitors to this remarkable place,” Hasegawa says.

“There’s some of the obvious things … and there’s also some of the small things.”

—Jessica Murphy, Seattle Waterfront Program CM, speaking about the engineering challenges of the redevelopment

Jessica Murphy, the city’s waterfront program construction manager, notes that the Marion Street pedestrian bridge services the country’s busiest ferry terminal, while the Union Street Bridge “is shoehorned into a street and next to massive underground electrical infrastructure.”

But many technical achievements are less noticeable. “There’s some of the obvious things, like our bridges that are all unique,” she says. “There’s also some of the small things, like trying to incorporate urban design elements into a basic roadway sidewalk design—such as how you attach steel edging for planters to sidewalks and pavements or tree pick guards or benches or railing and guardrail or precast benches. There were no [preexisting] standards. We had to create it all new, and you have to do that with thought and intention of how you want to maintain it.”

Other subtler highlights include exposed large aggregate surfaces for the pathways, notes Brian Kittleson, construction engineer with HNTB. “Here on the promenade, all the large exposed aggregate is at a 59-degree angle to mimic the actual 59-degree angle on the piers,” he says. It’s not that it was difficult; it’s just really careful timing and installation.”

The promenade features steel bands running along some intersections along with the aggregate pavement. “We have hard trial bands running in opposite directions, and then we have the 59-degree large exposed aggregate on a very flat area,” says Kittleson. “So the sequence would be to install the steel legend first, then do the hard trial bands and then match grade with the large exposed aggregate. It took a lot of practice ahead of time to get the mix design and the placement techniques correct to get the look we have today.”

A couple of waterfront-related projects are ongoing. One is a public–private partnership to connect and revitalize public parks north of the central waterfront. The $45-million Elliott Bay Connections project will be complete by June 2026, according to the city.

Construction began this year on the Bell Street Improvements project, including a protected bike lane, widened sidewalks and the removal of a travel lane. Moreover, the city plans to restore and reuse the salvaged historic sign that formerly stood on the Alaskan Way Viaduct.