1. Introduction

The brittle failures occurred at the beam-column joints of numerous conventional soldered steel frames during the Northridge earthquake. As shown in Figure 1(a), this conventional connection incorporates a shear plate bolted to the beam web and sites the welds in joint core area. Investigations conducted in the 1970s demonstrated that this connection was in possession of acceptable ductility under reciprocating load. The connections were low-priced, simple to manufacture, and diffusely applied to seismic-resistant steel moment-resisting frames (MRFs). After the Northridge Earthquake, the brittle damage was discovered in a large number of constructions that used site-weld connections. Typically, this damage began at the full penetration weld between the beam bottom flange and the column flange. From the results of postearthquake survey, it has been demonstrated that the main reason for these failures was the inferior ductile rotation capability in these welded connections. Although the damage in these conventional welded connections did not result in the collapse of buildings directly, its frequency was considerably high to attract the attention of researchers and designers.

After the earthquake, many researches have been conducted, aiming to put forward the alternative connections and the methods about the damage assessment and maintenance. The nonbonding posttensioned (PT) steel strands were applied to the moment-resisting connections in the prefabricated concrete structures by some research at the same period with the post-Northridge MRF investigation [1]. Considering the self-centering property and energy dissipation, many new moment-resisting connections were proposed. These researches climaxed with a quasi-static test of a large-scale prefabricated concrete structure with PT beam-to-column connections [2]. A major property of these connections was the ability to eliminate or reduce residual deformation by PT force, even if the obvious plastic transitory deformation took place under the quasi-static loading. In a later research, Ricles et al. [3] extended the conception of PT prefabricated concrete connection proposed by Priestley [1] and presented the development of a PT seismic-resistant connection for the steel frame, as shown in Figure 1(b).

The previous studies have confirmed the satisfying properties of self-centering systems, such as the following: (1) they avoid the use of field welding; (2) the stiffnesses of these connections are similar to those of soldered moment-resisting connections; (3) these connections are made with conventional materials and skills; (4) these connections are self-centering, which can significantly decrease or even eliminate residual drift; (5) the connections can localize damage, allowing easy repair following an earthquake; (6) the component dimensions and the complexity of structural skills of the self-centering steel moment-resisting frames (SC-MRFs) are similar to those of the MRFs with the welded connections. Therefore, the self-centering systems can be a practical alternative to the conventional frame systems.

In recent years, many studies about self-centering systems have been conducted. In this paper, a review about the self-centering steel frame systems including self-centering connections, braces, and full frames for seismic-resistant structures is presented in categories. The structural and test details and pivotal conclusions of many researches in recent years are introduced. Furthermore, based on these introductions, some summary and comments about these studies are conducted and proposed, aiming to provide the suggestions for the further study. Moreover, some critical issues in this field which need further investigation are summarized at the end of this paper.

2. Components and Mechanisms

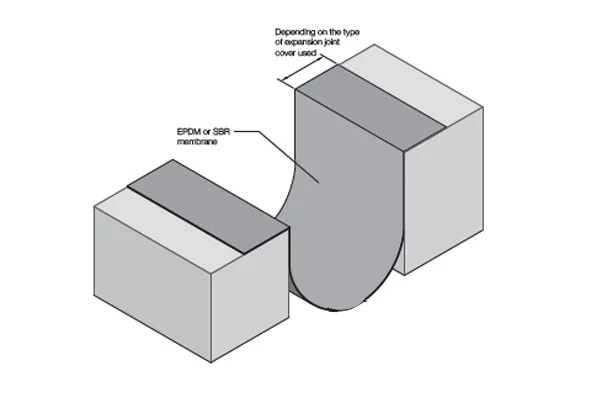

As shown in Figures 1(b) and 1(c), the SC-MRF consists of steel beams, steel columns, PT strands, energy dissipation (ED) devices, shim plates, and reinforcing plates. The strands provide tension force for the connection to implement the self-centering capacity. Meanwhile the friction between the beam and column contact surface resists the shear force transmitted from beam. The ED device dissipates energy and assists in resisting shear force and moment. The reinforcing plates can prevent the beam-end flanges from yielding under a relatively large compressed force after gap opening.

Figure 2 shows a conceptual moment-relative rotation (M − θr) relationship of the connection (proposed in [3], as an example), where θr is relative rotation between the beam and column. Before the gap opening, the flexural stiffness of this connection is similar to that of a conventional connection. The compression at contact surface will be exactly eliminated under an increasing moment before gap opening (decompression, event 1). The stiffness after decompression is associated with the ED members and PT strands. With the increase of the applied moment, the ED components are yielding at event 2, and the PT strands are ultimately yielding at event 5. The connection stiffness of event 3 to event 5 is approximately constant, which mainly depends on the elastic stiffness of the PT strands. Unloading at event 4, the gap will eventually close restrained by the tension force in strands (event 8). The ED devices dissipate energy in the whole process of gap opening and closing. An inverted loading can result in the same M − θr relationship on opposite direction. Other types of self-centering connections with the different energy dissipating devices and self-centering components work similarly.

The self-centering braces that consist of bracing members, self-centering elements, and ED devices are innovatively proposed and applied to steel MRFs to reduce drift and dissipate energy. Figure 3 illustrates the behavior of a self-centering brace. It is assumed that the system is restrained by a hinged bearing at the end region, and a force P is applied on the brace. The initial axial stiffness of the self-centering brace is the sum of the axial stiffnesses of the bracing members and self-centering elements. When the initial force provided by the self-centering elements and ED device is transcend, the bracing members begin to move relatively as shown in Figure 3(b). The stiffness of brace is distinctly decreased, while the ED device starts to consume energy through friction or yielding mechanism. The self-centering force increases with the increase of the relative movement between two bracing elements and will eventually be equal to P and provides the self-centering capability for the system after unloading. With proper design, the self-centering brace will move to its initial position as shown in Figure 3(c). An inverted loading can result in the same behavior on opposite direction as shown in Figure 3(d).

3. Self-Centering Connections

A PT connection, which can achieve excellent self-centering and acceptable energy dissipation capacity, is one of the most critical parts in a SC-MRF system.

3.1. Connections with Yielding ED Devices

Ricles et al. [3] extended the conception of the PT prefabricated concrete connections and presented the development of a PT seismic-resistant connection bolted top-and-seat angles aiming for dissipating energy by yielding under cyclic loading. Three FE models with different angle size, gauge length, and posttensioning force were established and analyzed. Then this connection was utilized in a full six-story, six-bay frame model that was simulated under the EI Centro and Newhall ground motion. The time-history analyses’ results indicated that MRF with these connections possessed acceptable self-centering capacity, stiffness, strength, and ductility.

The quasi-static tests on nine large-scale specimens were performed by Ricles et al. [6] to study the behavior of a posttensioned wide flange connection equipped with ED angles. The connections exhibited good self-centering capacity, elastic stiffness, strength, and ductility under quasi-static loading. Thereafter, new types of PT connections with bolted ED angles were investigated analytically and experimentally [7, 8]. Some of the experimental results validated that the columns and beams remained elastic, while plastic strain occurred on the angles to consume energy under a relatively large drift. These self-centering connections introduced in the above three researches can possess satisfactory ability when well designed. However, investigation on the design method of these connections is relatively deficient, which is the main factor hindering the practical application of this kind of connection.

The precise FE models used in self-centering connections with the angles were extremely time-consuming. Aiming at conquering that deficiency, a simplified numerical model was introduced by Chen et al. [9]. Furthermore, Xi and Ju [10] proposed a utility theory approach to calculate the moment-relative rotation relationship of this connection. The simulation results of the simplified numerical model [9] based on ANSYS can agree well with those of the elaborate model by adjusting the thickness of the angles. However, the theoretical method used to calculate the adjustment value of the thickness of the angles was not proposed, and the adjustment value was obtained by several times trial calculation, which partly reduced the practicability of the model.

A parametric study based on the results of FE analysis combined response surface methodology (RSM) was performed by Moradi et al. [11]. Some of the analytical results indicated that a high PT force enhanced the initial stiffness, strength, and self-centering capacity but reduced the ductility of PT connections. Another parametric study was performed by Shiravand et al. [12], aiming to study the effect of angle sizes on behavior of the self-centering connections under quasi-static loading. The FE models were compared to the previous experiments on self-centering connections with ED angles performed by Garlock et al. [13] and Zhang et al. [14] to verify these models. Results indicated that angle sizes significantly affected the behavior of these connections compared to other parameters. The energy dissipation increased by approximately 10% with the increase of the thickness from 18 to 22 mm. Increasing angles thickness greatly enhanced the ED capacity but decreased the self-centering capacity of the connections. The utilization of the angles with different shapes of the stiffeners can significantly increase the ED capacity of connection. But, worryingly, the beam instability and excessive local stress in the regions of beam and column near the stiffeners may occur when the oversize angle stiffeners are used. Therefore, it is essential to set up an upper limit of the size of the angle stiffeners.

A new posttensioned T-stub connection (PTTC), as shown in Figure 4, was proposed and analytically investigated by Aliabadi et al. [15]. Parameter studies proved the acceptable self-centering capacity of the PTTC. Saberi et al. [16] proposed the bolted T-stub connections equipped with weak bots and T-stubs. Similar to the ED angles introduced before, the plastic hinges will occur on the T-stubs as shown in Figure 4 in the case of the connection gap opening, providing a reasonable energy dissipation. To prevent the plastic hinge from occurring in column bases, the bolted T-stubs were also used in column base connections [17]. As shown in Figure 4(b), the connections can achieve excellent self-centering capacity with different levels of the total PT force in the strands (900 and 1525 kN). The simulation results showed that the self-centering behavior of these connections could decrease or eliminate inelastic rotation and provide essential strength and stiffness in a great earthquake. As shown in Figure 4(a), the area of the plastic hinge regions in a T-stub is larger than that in an angle; therefore, the theoretical ED capacity of a T-stub connection is relatively better than that of an angle connection. Correspondingly, the total posttensioning force in strands used to provide the recentering behavior is relatively larger, meaning that the larger column and beam sections are needed.

An innovative self-centering steel PT connection using hourglass-shaped metallic energy dissipaters (WHPs) was investigated analytically and experimentally by Vasdravellis et al. [18, 19]. Some of the experimental results showed that this connection eliminated residual deformations and kept beam in elastic range when the story drifts were smaller than 6%. Furthermore, the column base joints with WHPs were investigated by Kamperidis et al. [20]. The experimental results demonstrated the potential of the column base to reduce first-story residual drifts and protect column bases from yielding. The energy dissipation mechanism of the connection with WHPs is identical to that of the connection with angles, and both are material yield (plastic hinges) limited in a certain ED component. However, the layout of WHPs will consume some space between top and bottom beam flanges and may limit the number of the strands that can be installed. Some other self-centering components such as prepressed spring or SMA bolts can be used, which can be installed on other places of the beam except both sides of the beam web.

The performances of ten hexagonal castellated beam specimens in self-centering connections with bolted top and bottom angles, as shown in Figure 5, were investigated analytically by Sarvestani [21]. The FE models were validated against the experimental study conducted by Garlock et al. [13]. Some of the simulation results showed that self-centering connections applied to these beams possessed higher strength with smaller weight compared with the conventional solid-web beams.

The plastic hinges will occur on the yielding ED devices when the structures are subjected to an earthquake. It can be concluded from the above research that yielding ED devices can provide abundant and stable energy dissipating capacity for the SC-MRFs. However, they are usually arranged on the top and bottom flanges of the beam, which will make them come into contact with the floor slabs. It may affect the self-centering capacity of the connections. They are usually damaged and should be replaced after an earthquake.

3.2. Connections with Friction ED Devices

The ED devices that dissipate seismic energy by metallic yield are easy to damage when they suffer an energy input. Rojas et al. [22] proposed a friction-based ED element that transformed earthquake energy into heat with friction mechanism, preventing ED devices from damaging after consuming energy. Two brass shim plates sandwich a steel plate and these three plates are bolted by the prestressed high-strength bolts to produce friction force during loading. A simulation model of the connection was established and then added to a six-story, four-bay frame model, which then was subjected to 8 different ground motions. It was analytically demonstrated that posttensioned friction-damped connections (PFDC) possessed acceptable energy dissipation, self-centering capacity, strength, and superior seismic performance compared to that of the welded connections. But there is still a critical issue in this system which is how to design the bolt prestressing force to achieve both reasonable energy dissipation and good self-centering capacities.

The connections with friction devices can be interfered by floor slabs. For improving these connections, Wolski [23] developed a bottom flange friction device (BFFD) connection, in which the friction-based ED device was installed on the column and the bottom beam flange assisted ED angles were bolted to the column and top beam flange, as illustrated in Figure 6. In a later research, Wolski et al. [24] performed seven large-scale experiments to study the influence of the BFFD friction force, connection details, and loading on the behavior of this connection. Some of the experimental results indicated that ED capacity, initial stiffness, and recentering capacity of the connections were significantly affected by the friction force provided by ED device, which were reflected as higher friction force provided a higher ED capacity and initial stiffness but a lower self-centering capacity. The unsymmetric arrangement of the BFFD can avert the interaction between the floor slab and connection but will lead to the asymmetry of the hysteretic behavior. It may bring about adverse effects under dynamic loading.

To study the behaviors of the BFFD connections, an analytical model was proposed by Guo et al. [25] and Song et al. [26]. Compression between slotted plate and prestressed bolts, which were not considered in earlier numerical simulations [22, 27], was simulated by assigning numerous parallel Elastic-Perfectly Plastic Gap (ElasticPPGap) objects for the truss elements (friction elements), as illustrated in Figure 7. Only when the strain of friction elements ε surpasses the predefined value ε0 can ElasticPPGap material take effect. It was validated that the simulated results could fit with experiments acceptably. The yielding of the bolts caused by the extrusion against the slotted plate was simulated in this research. It can be noted that the extrusion occurred under a relative rotation that was not very large (0.035 rad). Therefore, a relatively large size of the slotted hole should be selected to accommodate the movement of bolt.

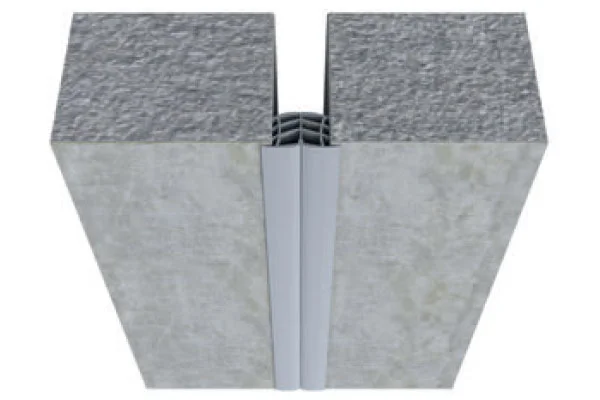

An analytical model for a PT connection with bolted web friction devices (WFDs) was developed by Tsai et al. [28]. The experimental research of the PT connections with these ED devices was performed by Tsai et al. [29] and Zhang et al. [30]. Figure 8 shows the configuration of these connections, which consist of two web clamping plates welded to column flanges and bolted to beam webs by frictional high-strength bolts. Tests confirmed a stable hysteretic performance of the bolted WFDs under cyclic loading. Zhang et al. [14] developed a prefabricated self-centering (PSC) connection with WFDs, which was appropriate for the high-rise constructions. Low-cycle loading experiments and relevant theoretical analyses were conducted with the finding that the residual deformation of this connection was minute (the maximum residual gap opening width is equal to 1.24 mm), demonstrating a similar and satisfactory recentering capacity of a PSC connection compared with other PT connections proposed previously. The utilization of the washers is requisite for the friction device to avoid the instability of the friction behavior. Similar to BFFD connections, a sufficient size of the slotted hole in the beam web should be designed to avoid the interaction between the bolt and web. There may be a concern about whether the ED capacity can be preserved after exposure to high temperatures, which will cause the expansion of bolts and reduce the prestress in bolts.

A self-centering sliding hinge joint (SCSHJ) with friction damping ring springs, as shown in Figures 9(a) and 9(b), was developed by Khoo et al. [31]. For further investigating the performance of these connections, the experiments on an interior connection subassembly were conducted by Khoo et al. [32]. As shown in Figure 9(c), the ring spring joint (the percentage of the joint moment capacity developed by the ring spring PRS = 100%) possessed a better self-centering capacity but a relatively inferior ED capacity compared to the SCSHJ with PRS = 54.2%. The SCSHJ actually is the combination of sliding hinge joint and ring spring joint which has relatively good energy dissipating and recentering capacities, respectively. However, a significant decline of recentering capacity was observed in SCSHJ with PRS = 54.2% as shown in Figure 9(c). Therefore, the prestress in ring spring should be increased to provide sufficient self-centering force that is larger than the resistance in SHJ joint.

The friction energy dissipation devices were also used in beams and column bases because of their reliable ED capability. Deng et al. [33] developed a self-centering coupling beam equipped with four friction dampers as ED devices, aiming to eliminate the beam elongation effect. The significant rocking mechanism was observed at the 3.3% shear deformation angle, indicating that the beam elongation effect was circumvented. However, significant PT force loss (with the maximum value equal to 47 kN) caused by the small length of the strands occurred during the cyclic loading, which may reduce the efficiency of this system. To conquer the phenomenon of PT frame expansion caused by the gap opening and closing on the beam-column interface, Huang et al. [34] introduced an innovative friction-damped self-centering coupled beam (CB). Chou and Chen [35] introduced a three-dimensional analytical model with rotational springs in the PT column bases. Freddi et al. [36] presented a rocking damage-free steel column base using the tensioned high-strength tendons to provide rocking characteristic and friction-based ED devices to consume seismic energy. The behavior of PT column base connection is limited by the relatively small space for the arrangement of self-centering components. A fewer number of PT strands with small length are able to be anchored because of the limitation of the space, which may lead to a significant loss of PT force and residual rotation of the column base.

There is no significant damage on friction device after consuming energy; therefore, it can be reused with only supplementing the pretightening force of bolts. The energy dissipating capacity of the friction device can be greatly affected by the pretightening force in bolts. However, the pretightening force may reduce when suffering a high temperature or long-term vibration, especially in some peculiar industrial constructions. A regular inspection of the pretightening force is needed for the SC connections with the friction devices.

3.3. Connections Using Shape Memory Alloy (SMA)

By applying the typical properties of SMA materials which are superelastic and can return to their original sizes after deformations, a variety of seismic-resistant devices such as dampers [37–40], braces [41–43], and base isolation [44, 45] have been proposed. Recently, a growing academic concern has been given on SMA-based self-centering systems in which SMA can be utilized in two ways: (1) SMA as both ED elements and self-centering members such as SMA bolts and ring springs and (2) SMA as self-centering members such as tendons or rods.

Chowdhury et al. [46] innovatively used the shorter-length tendons in connection proposed by Ricles et al. [6]. For avoiding reduction in the self-centering capacity due to yielding of steel strands, the utilization of SMA strands was proposed. The experiment results demonstrated that connections with shorter-length SMA strands (FeNCATB alloy, with the length of 1019 mm) produced higher strength, stiffness, and ED capacity (97.26 kNm at a story drift of 3.5%) and were effective in retaining self-centering force. The maximum moment capacity was 451.55 kNm, which was only 7.35% smaller than that of the connection with a strand length of 3057 mm. However, the capacities of different SMA alloys vary greatly. For example, NiTi and FeMnAlNi alloys whose moment capacities are relatively lower are not suitable for the self-centering connections as recentering components like strands.

To prevent significant plastic deformations from occurring in ED members, the SMA angles were proposed and applied to self-centering connections by Chowdhury et al. [47]. The test results showed that the SMA (FeNCATB alloy) angles could reduce residual displacement of ED elements in which the recover strain could reach 13.5%. However, because of the higher plasticity index and rupture index [48] for SMA angle connections compared to corresponding steel angles, the probability of plastic deformation cumulation and fracture of bolts after a violent earthquake is relatively higher. Moreover, the energy dissipation capacity of the SMA angles is generally lower than that of the steel angles. One more ED device can be considered to be added in this connection for a better energy dissipation capacity.

To reduce the plastic strain of link beams, a self-centering link beam with posttensioned SMA rods was developed by Xu et al. [49]. There are two basic modularized configurations for ease of fabrication and erection, as shown in Figure 10. For type I link, both two link-end connections apply separated SMA rods, which anchored on the rotatable link beam and corresponding region of a connection, respectively. For type II link, the SMA rods pass through the whole rotatable link beam and are anchored on the regions of connection with both ends. The effect of the parameters including the length of the link and the SMA rods, the areas, and prestress of SMA rods were investigated. Part of the simulation results showed that the length of the link and area of the SMA rods were the relatively critical parameters in designing this system, which significantly affects the strength of the self-centering link beam. It has been demonstrated that this link beam with self-centering elements could be designed to perform comparably to the traditional link beams. For type I link, the short length of the SMA rods may result in an excessive large stress in rods and rotation centers of link beam. It may be the good schemes to weld reinforcing plates at the end of the link beam or increase the length of the SMA rods to avoid the yielding under a relatively small drift.

Wang et al. [50] experimentally investigated an innovative connection applying an SMA ring spring system. As shown in Figures 11(a) and 11(b), the elastic force in ring spring provides moment-resisting and self-centering capacity for this connection. Every ring spring system consists of several SMA outer rings and matched HSS inner rings. As shown in Figure 11(c), the ED capacity of this connection largely depends on the thickness of the outer ring. This connection showed acceptable cyclic performance under quasi-static loading. However, unexpected fracture on outer ring in large drift ratio occurred, which meant a necessity of replacement after a violent earthquake.

Equipped with an SMA ring spring damper, a new type of asymmetric self-centering connection inspired by Khoo et al. [31, 32] was presented by Feng et al. [51], as shown in Figure 12. The moment resistance and self-centering force are offered by an SMA damper that is fixed on the flanges of column and beam through a pin shaft and a bracket, respectively. The experiment results showed that this connection possessed a favorable ED and self-centering capacity, although slight inclination of the SMA rings occurred during the cyclic loading. There is an ultimate deformation for these ring spring systems [50, 51]. When the drift exceeds the limitation, the stiffness of the connection will increase sharply as shown in Figure 11(c), and the flexible connection transforms into a rigid one on the loading direction. It may result in significant yielding of the beams. The protection mechanisms of this limit state can be further investigated.

The SMA bolts with a superelastic property can provide moderate ED capacity for the connections [52]. The self-centering connections using SMA bolts were tested by Chowdhury et al. [47], Wang et al. [53], and Fang et al. [54, 55] through experimental and numerical investigations. It was found that load capacity, initial stiffness, and ED capacity were significantly related to the diameter, prestressed force, and length of SMA bolt. Wang et al. [56] presented an innovative steel column applying NiTi SMA bolts, as shown in Figure 13. The top and bottom ends of the SMA bolts are fixed on the base plate and the foundation, respectively, and can be easily checked and replaced. SMA bolts can provide a flag-shaped behavior for this column-base connection with only inelastic strain occurring on the bolts while column remains elastic after loading. It should be noted that the threads are the weaker part of the SMA bolt, where fractures may first occur.

4. Self-Centering Energy Dissipating Braces

The concept of self-centering energy dissipating (SCED) bracing system was previously developed by Christopoulos et al. [5]. The system comprises traditional steel bracing elements, an ED device system, and a tensioning system. Validated by the results from the tests on a full-scale frame system, the proposed SCED brace could achieve a dependable self-centering hysteretic response. To address the drawback of conventional yielding system, which will undergo the extensive structural damage and possibly substantial residual deformations after a design level earthquake, the SCED bracing system has been widely developed.

4.1. Self-Centering Braces with SMA Materials

The large-scale self-centering buckling-restrained braces (SC-BRBs), as shown in Figure 14, were designed and tested by Miller et al. [57]. An SC-BRB is composed of a typical buckling-restrained brace (BRB) system and prestressed superelastic nickel-titanium (NiTi) SMA rods, which are connected to the BRB by series of concentric tubes and moveable end plates. The test results indicated that NiTi SMA SC-BRBs provided dependable and repeatable hysteretic response with acceptable energy dissipation (with the maximum value equal to 378 kJ) and self-centering capacity. Inevitably, the loss of SMA pretightening force will occur during the loading process, which is induced by the development of the lower plateau region of SMA behavior under increasing maximum strain. A proper increase of the SMA rod length may alleviate this issue.

Kari et al. [58] proposed a simple-to-mount SC-BRB, in which the self-centering force and the energy dissipating capacity were provided by SMA wires. For studying the seismic behavior of the whole structure, the SC-BRBs were incorporated into four building models designed by Kiggins et al. [59] and Teran-Gilmore et al. [60]. The simulation results showed that a frame equipped with SC-BRBs possessed a larger lateral stiffness with smaller residual deformation.

Haque and Alam [61] proposed a system known as the piston-based self-centering bracing (PBSC brace) system [62]. The PBSC brace consists of two concentric steel elements connected to a cylinder piston assembly though superelastic SMA bars. Four PBSC braces with different diameter of the SMA bars, 10, 12, 16, and 20 mm, were simulated, with the finding that the maximum strength of the brace increased with the increase of the diameter (110, 160, 272, and 453 kN, respectively). The simulation results showed that the PBSC brace hysteresis possessed symmetry about both story drift and resistant force behavior and indicated an acceptable hysteretic behavior. However, the theoretical maximum length of SMA bars applied in the PBSC brace system is equal to half of the brace length, which means that the maximum extension capability of this bracing system will be half of that of the SMA bars.

It can be summarized from the above researches that the application of SAM alloys as strands, rods, and tendons in self-centering connections and braces can reduce the loss of posttensioning force compared to the steel strand with the same length. However, one of the most prominent issues of the application of SMA alloys in civil engineering is their high price. With the development of material science, the production cost of SMA alloys will decrease, which makes them have the potential to become a wildly used material in the high-performance buildings in the future. Because of the superelastic character of SMA alloy, current studies ignore the situation that the deformation of SMA may exceed the elastic strain and the hardening may occur, which may affect the seismic behavior of the construction. And this case should be considered when a considerably large strain of SMA may be achieved.

4.2. Self-Centering Braces with Tendons or Strands

For surmounting the limited elongation capability of tendons, an enhanced-elongation telescoping SCED (T-SCED) brace was developed by Erochko et al. [63]. The brace possessed twice elongation capacity of the common brace and could accommodate 3.9% story drift in the test frame. Based on load tests in a full-scale vertical steel frame, the T-SCED brace behaved stably and symmetrically, maintaining an intact self-centering capacity until nearly 4.0% relative rotation. Erochko et al. [64] developed a model that considered the effect of axial member length tolerances to simulate the cyclic behavior of both conventional SCED braces and T-SCED braces. However, the behavior of SCED braces may be sensitive to the fabrication tolerances that make the length of the inner and outer members never be equal. Hence, a proper range of the fabrication tolerance should be investigated based on both brace behavior and economical efficiency.

Zhou et al. [65, 66] experimentally investigated the hysteretic performance of self-centering buckling-restrained braces (SC-BRBs) equipped basalt fiber-reinforced polymer (BFRP) tendons. The elastic elongation of BFRP tendons caused by the relative movement between two tubes generated an elastic resilient force and a trend to return to the initial position after unloading. The experiment results demonstrated that the self-centering brace with BFRP tendons possessed repeatable hysteretic response and good self-centering capacity. However, for the BFRP-SC-BRBs, the minor gaps between components introduced during fabricating the brace may result in the unrecoverable deformation. The relatively high machining accuracy should be guaranteed to avoid excessive residual deformation.

Zhou et al. [67] proposed an elastic-plastic model utilized for analysis of the SC-BRBs cyclic behavior. Nevertheless, this model was not able to consider the effect of many nonlinear factors including contact, friction, large deformation of geometry, and component damage. To study the influence of crux structural parameters on the cyclic behavior of SC-BRBs, an FE model was constructed by Xie et al. [68]. Some of the results demonstrated that the displacement capacity was large dependent on the elastic maximum elongation rate of the prestressed tendons.

Wang et al. [69] proposed a simplified SC-BRB. The utilization of the cross-anchored prestressed steel strands was the main difference from other SC-BRBs [66, 70]. The prestressed steel strands are anchored on the inner tube using cross-anchored technology that could improve the deformation capacity of this bracing system. Some of the experimental results validated that the SC-BRBs could provide an acceptable energy dissipation and a good self-centering capability when subjected to a displacement lower than (1/100) of the brace length. It is important that the posttensioning force of the strands should match with the dimension of the core plates to ensure the acceptable energy dissipating and self-entering capacities of the braces.

Chou et al. [71–73] proposed a new steel dual-core self-centering brace (DC-SCB), utilizing three steel bracing members, two friction devices, and self-centering elements, as shown in Figure 15. The steel bracing members and self-centering elements were arranged in parallel in the DC-SCB to enhance the axial elongation capability of the SCED bracing systems [5] if the identical self-centering elements were applied to these two braces. Chou et al. [74] put forward a DC-SCB processing a flag-shaped cyclic response with small residual deformations. A steel MRF that equipped this DC-SCB was subjected to quasi-static loading without damage in main components [75], which validated a favorable seismic performance of this self-centering system. A relatively low deformation capacity has been observed in fiber tendon with large diameter, so only small-diameter fiber tendons are recommended to utilize in this self-centering system. Furthermore, steel strands or SMA tendons can also be attempted as the self-centering components of this kind of brace.

Aiming to reduce cost and simplify the structure of self-centering braces, Dezfuli et al. [76] proposed a new type of core-less self-centering (CLSC) brace that minimized residual deformations by combining nonlinear elastic behavior with the nonlinear inelastic behavior of traditional steel MRFs. Several pairs of symmetrical cables are attached to a round anchorage plate for recentering, as shown in Figure 16. The one-story, one-bay frames equipped with the CLSC brace and steel plate wall with four different self-centering ratios αSC (0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 5.0) were simulated, respectively. The results showed that this CLSC brace was relatively economical and could enhance structural resiliency compared to the steel plate wall. The utilization of the CLSC braces could significantly debase structural restore expenditure with minimal manipulation of structural performance parameters. However, for the structures equipping self-centering braces, the stiffness increases, while energy dissipating capacity decreases with the increase of the self-centering ratio. Therefore, the efficient optimization methods of the arrangement of the self-centering brace are important for the design of these structures.

The prestressing loss during time is a general issue in these posttensioning components including PT strands or tendons. Until now, supplementing the prestressing periodically is one of the few effective ways to relieve this issue. Furthermore, to circumvent the prestressing loss, the springs systems have been utilized as the self-centering components instead of the PT strands in many researches that have been introduced (researches [32, 50] for self-centering connections and researches [77–84] for self-centering braces). The prestressing loss during time is still a critical question in the self-centering systems. The prestressing loss during the cyclic loading is observed in research [33] in which the strands were relatively short. While this prestressing loss was not general, for example, it was not observed in research [6] in which the strands were relatively long. Fortunately, the prestressing loss during the cyclic loading has little effect on the self-centering capacity according to the test results of research [33].

4.3. Self-Centering Braces with Prepressed Spring

Xu et al. [77, 78] proposed a prepressed spring self-centering energy dissipation (PS-SCED) bracing system, in which the springs were compressed at initial position by a pair of spring plates fixed on both ends of a spring to provide self-centering force, as shown in Figure 17. The ED devices based on friction mechanism were connected to two tube members by welding. The axial force in the disc spring increased linearly with the increase of the axial deformation. The initial state of the spring can be recovered without any prestressing loss. Quasi-static loading tests’ results indicated that this brace exhibited stable and repeatable self-centering and cyclic response with some effective energy dissipation. However, the junction plates are likely to buckle under a relatively larger axial deformation. It is a concern that the self-centering capacity may be significantly affected in this case. Hence, the reinforcement measures, for example, welding reinforcement plates on it or increasing the thickness, are needed to enhance the capacity of the junction plates.

Further studies by Xu et al. [79, 80] on the PS-SCED brace have been conducted, presenting the mechanics and experimental validation. Figure 18 illustrated the cyclic response of the PS-SCED bracing system, which could be regarded as a synthesis of the cyclic property of both the ED device and spring system. A proposed brace was tested with four different friction levels (0, 150, 200, and 300 kN, respectively) of the friction ED device, with the finding that the energy dissipation increased, while the self-centering capacity decreased significantly with the increase of the friction force. The test results showed that self-centering force provided by the springs was adequate to eliminate the residual deformations before the tube members yielding occured and validated that this bracing system was able to provide sufficient deformation capacity to consume energy during earthquake.

Xu et al. [78] presented an idealized piecewise-linear restoring force model to simulate the hysteretic behaviors of the PS-SCED bracing system. Furthermore, an original nonlinear mechanical model that made full use of an excellent numerical adaptability of the Bouc-Wen model was introduced to represent the recentering force, stiffness variation, and energy dissipation of the bracing system [81]. A coefficient that was related to the interaction in spring system was introduced in the proposed model. More recently, the ability of these models was evaluated by Fan et al. [82], indicating that both these models could efficaciously predict force-time responses and had the potential to design the PS-SCED braces. However, it should be noted that fabrication tolerances can cause the simulation result of the initial stiffness of brace slightly larger than the experimental result inevitably.

To abate the high sliding force and abrupt change in stiffness when expansion or compression of the SCED bracing systems occurs, Xu et al. [83, 84] introduced a novel self-centering variable-damping energy dissipation (SC-VDED) brace, in which variable damping was achieved by applying the magnetorheological fluid device. It was validated by the experimental results that the application of this ED device could significantly reduce the sliding force and enhance the energy dissipation capacity simultaneously. Combining with disc springs as the self-centering elements, this brace has the potential to provide a stable hysteretic response as well as the superior self-centering capacity.

For the braces or connections realizing self-centering capacity though prepressed spring systems, the losses of self-centering force during time or loading are not significant compared to those of the braces or connections realizing self-centering with PT strands or tendons. However, the assembly of the prepressed spring systems is relatively complicated and the demand on manufacturing accuracy of the components of these systems is relatively high. But it is worthy of the cost for some high-performance building.

5. Self-Centering Steel Frames

Roughly, there are two types of self-centering steel frame systems, namely, moment frame systems and braced frame systems. Both types of systems were proposed as good alternatives to conventional steel frames to reduce or eliminate residual drift and provide good energy dissipation.

5.1. Self-Centering Moment-Resisting Frames

A PT connection with ED angles for SC-MRFs was developed and extensively studied by Ricles et al. [3]. Time-history analysis validated that the seismic behavior of a posttensioned steel MRF was better than that of a typical MRF. Garlock et al. [85] proposed a performance-based design method for the SC-MRFs. A phenomenological model of ED angle connections that verified using prior experiments [6, 13] was applied in a two-dimensional model of the SC-MRF to conduct the economic loss assessment by Guan et al. [86]. The results showed that SC-MRFs with ED angles had a minor anticipated loss related to excessive residual deformations and a higher collapse loss compared to welded MRFs. The PT connection resists moment by gap mechanism, while the welded connection resists moment by the beam and panel zone, which results in a lower strength of a SC-MRF compared to that of a conventional welded MRF when their initial stiffnesses are equal.

Rojas et al. [22] performed inelastic analyses on a multistory and multispan steel MRF that equipped PFDCs to investigate its behavior under severe ground motions. By using fiber elements and springs to simulate the beams, column, and connection area, the seismic behavior of these PFDC-MRFs was validated to be acceptable in strength, residual deformations, and self-centering capability, although some yielding occurred at the column bases under design basis earthquake (DBE). However, a significant beam flanges yielding may occur at the end of the reinforcing plate under a DBE record, which will possibly lead to local buckling at this place. A ribbed stiffener is worthy of supplement in this place.

To investigate the seismic performance of a self-centering MRF with BFFD, static and dynamic analyses were conducted by Iyama et al. [87]. The results were compared to those of a similar frame with connections possessing symmetric behavior, with the finding that the dissymmetric property of BFFD-MRF increased the inelastic deformation of the upper flange of the beam, which might result in local buckling of the beam members. The nonlinear time-history seismic analyses showed that maximum and residual drifts of a BFFD-MRF were closed to those of a PFDC-MRF, validating a feasibility of this asymmetric connection. But the symmetric connection behavior as discussed in Section 3.2 results in the requirement of the larger beam sections or longer reinforcing plates for the top beam flanges to avert the flanges from buckling, leading to an expansion of the costs.

A 0.6-scale model of a two-bay SC-MRF test structure including WFDs was evaluated using the hybrid simulation method by Sause et al. [88]. Lin et al. [89] presented an overview about the experiment results and an assessment of the design approach. The SC-MRF performed well without damage during the DBE-level test, and the WFDs provided an acceptable energy dissipation capacity for this frame system. Some inelastic strain occurred when subjected to the maximum considered earthquake (MCE) and at least the collapse prevention (CP) performance level was realized. The incremental dynamic analyses (IDA) are indispensable to provide a broader reference to the design of SC-MRFs whose seismic behaviors under different earthquake records are highly random [90].

Zhang et al. [14] introduced a prefabricated self-centering steel frame (PSCF) containing WFDs applied in multistoried and high-rise structures. The PSCF could greatly improve construction efficiency. To enable frame expansion, Zhang et al. [91] proposed a spatial PSCF with a new type of floor system including sliding secondary beams. The test results demonstrated that these introduced PSCFs had satisfactory self-centering capacity and adequate redundance to resist multiple aftershocks. Significant local bucking occurred at the beam flanges and column bases when the maximum lateral displacement was achieved. But most part of energy was consumed by the WFDs; hence the frame still remained serviceable and overall collapse can be avoided because of the effectiveness of the PT strands.

The steel structures with SC-MRF using three different ED devices including top-and-seat angles, bottom flange friction devices, and web friction devices separately [4, 14, 24] were simulated under far-field and near-field ground motion by Sarvestani [92]. It was found that there was no significant distinction between the highest values of absolute and relative energy components when subjected to far-field earthquake, while the absolute energy components in these self-centering frame systems under near-field ground motion attained higher values than relative energy components.

Vasdravellis et al. [93] numerically assessed the robustness of a seismically designed SC-MRF in a column loss scenario. As shown in Figure 19, horizontal loading in one direction is resisted by SC-MRFs using stainless WHPs, which possess very high ductility [94] along the circumference of the frame, whereas bracing frames resist horizontal loading from the perpendicular direction. The simulation results showed that the exterior column adjacent to the removed column was susceptible to excessive beam web yielding and plastic hinge formation on the base, indicating that an enhancement of the external column was demanded if collapse was a potential threat when suffering a severe earthquake. The ability of SC-MRF to resist collapse is related to the degree of conservation of design. Smaller dimensions of components such as PT strand or reinforcing plate lead to a faster invalidation of the frame under column loss. Hence, a conservative design is suggested, providing a higher security under the condition that a collapse is possible.

5.2. Self-Centering Braced Frames

Self-centering buckling-restrained braced frames (SC-BRBFs) have drawn an increasing attention due to their resilience in postearthquake repair. Eatherton et al. [95] computationally investigated the seismic response of 15 prototype buildings applying SC-BRB. Liu et al. [96] considered the trilinear hysteresis in the determination of the inelastic displacement ratio (CR) of the SC-BRBFs. Nazarimofrad et al. [97] analytically studied the seismic behavior of a steel braced frame with SC-BRB using SMA. The results indicated that the SC-BRB made of hybrid steel and SMA provided a higher ductility and smaller residual drifts of the buildings.

Chou et al. [98] discussed the test performance of the two-story steel dual-core self-centering braced frame (DC-SCBF), special mixed braced frame (SMBF), and sandwiched buckling-restrained braced frame (SBRBF) (design details of the prototype frame can be found in [99]). The experimental results showed that there was no damage on the DC-SCB or BRB. But a fracture of the beam flange adjacent to the joint of the beam web stiffener and gusset plate toe was discovered. The SMBF possessed moderate lateral stiffness, residual deformation, and energy dissipation among all frame specimens and was verified as a potential seismic-resistant frame system. However, it should be noted that the lateral torsional buckling may occur and lead to the crack near the junction of the beam web stiffener and gusset plate. This failure mode is brittle and hard to repair. A relatively conservative design of the beam may prevent this situation from occurring.

Concentrically braced frame (CBF) system is a stiff and economical seismic-resistant steel frame system with low ductility and a trend to accumulate residual deformation in earthquake. To enhance ductility and decrease residual drift, the self-centering concentrically braced frame (SC-CBF) was developed by Sause et al. [88]. Qiu and Zhu [100] derived the expression of constant ductility spectrum for the flag-shaped hysteresis model and integrated it with the concept of performance-based plastic design (PBPD) to arrive at a design method setting the peak story drift ratio as the performance index. Aiming to validate this design approach for structures of different heights, 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-story frames were designed by Qiu et al. [101] and subjected to ground motion records corresponding to DBE level. The analytical results showed that the SC-CBFs were capable of meeting the prescribed peak story drift ratio target and demonstrated that this design method was applicable to low-to-high-rise SC-CBFs.

Keivan and Zhang [102, 103] presented a numerical investigation of self-centering eccentrically braced frame (SCEBF) subjected to seismic excitation, aiming to study the nonlinear seismic system behavior of K-type, D-type, and Y-type SCEBFs. It was validated that SCEBF systems could be designed to possess strength and stiffness comparable to traditional steel EBFs while preserving plumbness subjected to DBE. Tong et al. [104] experimentally and analytically investigated the D-type SCEBF with replaceable hysteretic damping (RHD) devices. The experimental results revealed that the SCEBFs were capable of recentering.

Until now, the putative methods about selecting a proper amount of self-centering force, energy dissipating capacity, and section size are still lacking. Although the satisfactory self-centering and energy dissipating capacity can be achieved with the main components remaining elastic, the excessively conservative design in section of main components leads to the excessive waste of materials and the increase of the construction cost. However, it can be predicted that, with the progress of research and application, this issue will be addressed step by step.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

With the development for more than 20 years, the structures of the self-centering connections and braces have become considerably diverse. As the good alternatives to providing self-centering capacity, SMA material and prepressed springs have been studied increasingly in recent years, providing the new directions for the development of the self-resetting structure systems. For a deeper understanding of the self-centering connections and braces with SMA or prepressed springs, further researches are needed. Because SMAs are weak in shear, the sudden failure of SMA bolts at higher drifts will affect both the energy dissipation and self-centering capacity of the connections. Further study on proper design guidelines for such systems is also needed.

Notably, many earthquake records exhibit a vertical component with a peak ground acceleration well in excess of the corresponding horizontal value. The excitation of vertical motion can result in drastic variation in the axial force on the column, which may significantly affect self-centering and energy dissipating performance. Future research should address this issue.

The self-centering steel frames can provide excellent seismic performance and good postearthquake repair capability and are fundamentally different from traditional steel frames in design concept, structural members, and construction measures. Notably, there are still some issues that need to be further studied, including the following: (1) the gap opening at connections after decompression causes the “expansion” of the PT frame, requiring the slabs and floor diaphragms to accommodate the expansion; (2) the higher mode effects cause the sway of the steel frames, resulting in the amplification of the peak seismic force; (3) the building code provisions to guide the design and construction of self-centering structures have not yet been completely established; (4) for the systems in which self-centering capacity is provided by the prestress tendons or PT strands, evaluation of prestress loss with large lateral deformation or during time and the influence of prestress loss on seismic performance are of concern. Although some specific structural details and approaches have been proposed to reduce the impacts of these issues, further research is still needed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The present work was funded by the projects of the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0703600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51878552), and the Shanxi Province Key Research and Development Program on Industry Innovation Chain (2018ZDCXL-SF-03-03-01).

Data Availability

The literature data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.